Young architect Jorn Utzon was backpacking through China in the 1950s finding inspiration in the Buddhist temples in Datong and the imperial buildings in the Forbidden City. One day a serious-looking policeman stopped the young Dane demanding to see his travel papers. "Oh I'm sorry," said the charming man. "I have a personal invitation from Chairman Mao to visit China."

Utzon's friendly persuasion, albeit a blatant lie, worked many times on his China travels as he looked for ideas in the lead-up to designing arguably the most famous piece of architecture of the 20th century, the Sydney Opera House.

The icon's famous sails, shells and gull-wing designs originate from Utzon's Nordic roots. His father was a boat builder and Utzon understood how his ancestors, the Vikings, would turn the hulls of their old boats upside and transform them into buildings.

|

|

|

Danish architect Jorn Utzon, designer of the landmark Sydney Opera House. [file photo: China Daily] |

These strong nautical influences are clearly apparent when one watches the Opera House mysteriously "float" on Sydney Harbor, but not so obvious are the Chinese architectural ideas, which were also used in its cutting-edge design.

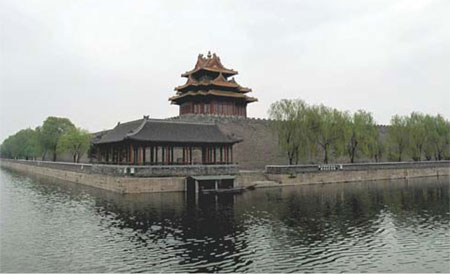

The floating effect used in the Forbidden City and set-piece construction promoted in a 1,000-year-old Chinese building manual were keys that opened the great Dane's mind and set free his architectural genius.

Details of Utzon's Chinese influences together with the Mao Zedong "invitation" anecdote were revealed by Utzon Center director Adrian Carter in Beijing this month when lecturing to architecture students about the genius of his educational institution's namesake.

Utzon passed away late last year, aged 90, but was still working with Australian architects on the Opera House's new interior, which returns the building to his original vision before he famously walked away from the project in 1966 after a row over planning and budget. The new $600 million renovation plan, which was announced in Australia last month, also involves lowering the Opera Theater floor by 18m and adding new interiors.

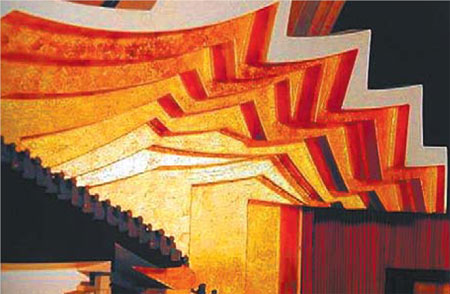

Before he died, Utzon revealed the festive Chinese colors he had in mind. "I am enthusiastic about the colors you find in Tibetan temples; the edge of orange just before it becomes red, or of violet when it becomes blue. I am thinking of the copper color of roofs that would be a wonderful color for the seating," he told a US magazine.

Last month in Sydney, at a special memorial service for Utzon, an image of his red interior design for the Opera Theater was projected above the stage hinting at what the future interior will look like.

The strong Chinese red color reflected the festive, celebratory mood he wanted to create. Utzon planned to create a climax of color that would uplift a visitor from daily life and the realm of the theater world.

|

|

|

Utzon's original interior design of Sydney Opera House used Chinese festive red, which is planned for the new renovation. [Courtesy of Adrian Carter] |

"He was fascinated by the very vibrant, dramatic colors used in China architecture. His interior is very festive and very alive," says Carter.

"The last 10 years he was working on new designs and was re-introducing his original Chinese idea. Sometime in the future the Sydney Opera House interior will be more like this."

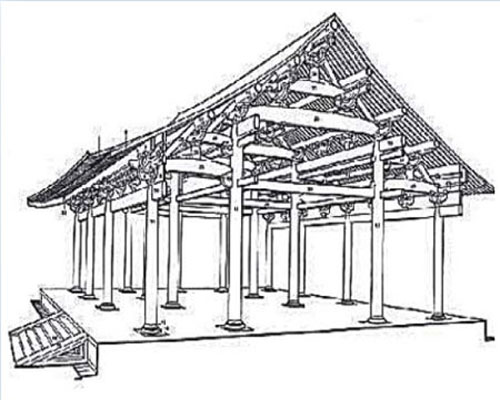

Utzon was first introduced to Chinese architecture as a student when he picked up an illustrated copy of the Song-Dynasty building manual Ying Tsao Fa Shi (building standards).

According to Carter, the 1,000-year-old text showed how a limited set of patterns could be used to build any structure, from a simple hutong home to an imperial palace to maybe even an opera house.

Utzon became so hooked on the manual, he returned to China to buy his own copy to take with him to Sydney during the Opera House's construction.

Under the set-piece design principles in the manual, all of the Opera House's roof shells come from a single sphere. One of his assistants revealed how Utzon explained this idea by cutting all the shell-shaped pieces from the skin of a single orange.

|

|

|

A sketch from the Song-Dynasty building manual Ying Tsao Fa Shi (building standards). |

Forbidden City architecture used a floating-cloud effect that also influenced Utzon's final design of the famous white shell exterior.

Carter says Utzon's side-by-side sketches of the Opera House and the Forbidden City reveal how the 500-year-old Chinese imperial palace inspired him. "I recently bought a text book used by architecture students and on the cover there is a picture of the Imperial Palace and also the Opera House, reflecting the old and the new," he says. "But I don't think the students realize the close relationship between the two buildings."

Utzon took ideas from all over the world and was strongly influenced by Mexico's platform temples used by the Yucatn, which featured huge, stepped approaches. The Sydney Opera House has a massive podium that forms the base. Other influences include the dome of Isfahan's Great Mosque, the fortified villages of Morocco and natural surroundings found in Japanese houses.

Carter says Utzon used nature as a teacher and believed buildings should be organic and harmonize with their natural surroundings.

One of the most powerful visual features of the Opera House is the glittering effect created by special tiles, which look like a fresh layer of snow with ice crystals shining on it.

Utzon once again traveled to China and Japan, looking at samples of ancient roof tiles and half-glazed ware because he believed the materials needed to come from the ancient building world, which had stood up to many years' use without deterioration.

|

|

|

The Forbidden City architecture with a floating-cloud effect influenced Utzon's design of the Sydney Opera House. [China Daily] |

When the Sydney Opera House was opened in 1973, Utzon was invited to the opening but declined and never set foot in Sydney again. Instead of establishing him as one of the world's most innovative architects, it almost ruined his career.

In 1957, when Utzon won the Sydney design competition, he was hardly known outside his native country. For the next five years he operated out of his Denmark office before moving his family to Sydney to closely monitor the mission.

Utzon's supporters say the New South Wales government underestimated construction costs, and as they rose and the project was delayed, he became a target for politicians pandering to suspicious local voters, who were still making up their minds over the merits of such a radical and expensive building.

When the government stopped paying Utzon in 1966, he left Australia and never returned.

"The real loss in the Sydney Opera House project is not the huge cost overrun in itself," wrote Bent Flyvbjerg, a professor of planning at Aalborg University in Denmark, in the Harvard Design Magazine in 2005. "It is that the overrun and the controversy it created kept Utzon from building more masterpieces."

Cater says that when Utzon returned to Denmark, the president of the country's Association of Architects told him his abandonment of the Sydney project was a disgrace and he wouldn't get work from the Danish government.

Utzon would receive only one other commission on the same grand scale as the Opera House, the Kuwait National Assembly, in 1971.

His genius was finally acknowledged in 2003, 30 years after the Opera House was opened when he was awarded the Pritzker Prize, the highest accolade in architecture.

The citation read: "There is no doubt that the Sydney Opera House is his masterpiece. It is one of the great iconic buildings of the 20th century, an image of great beauty that has become known throughout the world - a symbol for not only a city, but a whole country and continent."

(China Daily April 22, 2009)