Shanghai's Xintiandi set the bar (how high is disputed) for renovations of old areas for commercial use and a new audience. Now the architects behind it are working on their most ambitious project to date: Lingnan Tiandi in Foshan, central Guangdong Province.

With areas of pure preservation and more attention paid to integrating local customs, the project is partly a response to criticism of the Shanghai Xintiandi model, namely, "that it doesn't preserve enough, that it's too commercial, that it doesn't retain enough of the local culture."

At around 517,500 square meters, it's five times the size of Shanghai Xintiandi, the first of its breed of commercial preservations in China.

Its creator, American lifestyle architect Ben Wood, calls himself "a man on a mission." He is the chief architect behind Shanghai Xintiandi and founder of Ben Wood Studios.

Wood has created four other tiandis (literally "heaven and earth") in China, and Foshan in the steamy Pearl River Delta is the fifth.

Despite Shanghai Xintiandi's commercially lucrative nature, Wood sees his mission as recreating a more humane, outdoor lifestyle that is being eroded by modern high-rise, air-conditioned living.

In his Foshan Lingnan Tiandi, he is renovating an area of Lingnan architecture typical of southern China. Foshan, a city of 3.1 million, is the hometown of many overseas Chinese and is one of the country's four famous ancient towns.

Foshan is the biggest China attempt at the model, which refits historic architecture with modern interiors and turns them into entertainment, nightlife and shopping hubs. Shanghai Xintiandi proved its commercial viability.

Wood has worked with the same investor, Shui On Land, to develop the tiandi projects across China in Hangzhou (capital of Zhejiang Province), Wuhan (capital of Hubei Province), and Chongqing Municipality.

|

|

|

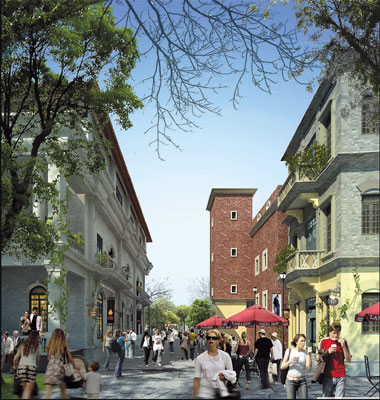

An artistic rendition shows Jianshi Village after renovation. [Shanghai Daily] |

The latest venture, however, presents special challenges. In the old heart of Foshan City, Lingnan Tiandi covers 517,500 square meters.

There's more variety of buildings, including a temple, theater, pawn shop and buildings housing medicine and wine guilds. There are even ancient, underground pottery kilns. The ancient city was known for gauze fabric, ceramics and traditional medicine.

For Wood, the tiandi projects represent neither the old nor current modern culture - it is about "creative renovation" in which design opens possibilities for an entirely new lifestyle.

"I call these developments 'romantic interludes'," says Wood. "We create places out of the ordinary where popular culture can be tried out."

The scale and variety of the project has allowed Wood to include new features, notably 10,000 square meters of pure preservation. The area is known as Donghuali and includes 60 courtyard houses more than 100 years old. It lies to the east of the new Lingnan Tiandi development, which connects this area to the ancient Zhumiao Temple in Foshan's old city center.

Compared with Shanghai's lane houses, traditional Lingnan houses are better preserved. Constructed of thicker, higher-quality bricks, they feature a high, curved and ornate roof while the rest of the house is of a simple, even austere design.

Unlike the rest of the development, which will refit historic architecture with mod cons for occupancy by restaurants, bars and shops, the courtyard houses will have full period details restored, and all modern changes removed.

Later they will be put to "passive" uses, such as art galleries that do not require intrusive facilities.

Wood's team plans to apply for a UNESCO world heritage listing for the area.

He wants to do this preservation right, but he is excited more by the possibility for innovation in the rest of the development.

"I am not a preservationist," he says.

"We shouldn't treat buildings as ancient relatives to whom we may have felt close as children, only to grow up and find that as adults we have nothing in common."

Over the past nine years working on tiandis across China, Wood says he has learned to quickly understand the focal points of the local lifestyle.

In architecture, the "where" is of paramount importance. "Would the Eiffel Tower be as beautiful anywhere but in Paris?" asks Wood.

To better learn about Foshan's characteristics, Wood personally moved into one of the traditional houses in its original dilapidated state. Since last August he has traveled between his Shanghai office and the Foshan house, and now spends two days there every week.

In the humid and hot southern China climate, two things struck him: the old custom of late-night oyster barbecues when the temperature cools and the erosion of this pastime by the all-pervasive air conditioner.

"Hong Kong high-rises have set a terrible example for southern China," he says, observing that over-reliance on air conditioning has led people to spend virtually all their time indoors. "I want to change how people view public spaces and show them that not everything has to be a glass-roofed mall. Instead, we can appreciate the outdoors and nature."

Tiandi developments are characterized by regenerations of an entire neighborhood, unlike conventional preservation efforts that concentrate primarily on one building. Strict guidelines require that the area's "framework" remains the same. This includes house structures - buildings don't get higher or lower, alleys remain the same width, no trees are cut down.

This retains the authentic atmosphere of traditional lane living.

While Wood lived in the rundown Lingnan house, he insisted on not installing air conditioning to experience what life would be like without this modern crutch.

He quickly understood the discomfort of the climate.

To find an innovative solution, Wood is embarking on outdoor air conditioning for Lingnan Tiandi. He is in talks with green companies that use evaporative cooling that passes hot air through water, which releases the heat as vapor.

Not only can this reduce outside temperatures by up to 15 degrees Celsius, but it also uses little energy and leaves almost zero carbon footprint. Thus, Wood hopes people can comfortably enjoy the outdoor neighborhood he has renovated.

As the economy develops, the Lingnan Tiandi area has also been gradually deserted. Residents moved into high-rise apartments and the social fabric started to unravel. Thus, another part of Wood's mission is to revive the community, the human activity in the area. It's a hard task, he says. "We're working from nothing."

Moreover, pleasure is always part of the "romantic interlude" of tiandi developments. To create a new social focal point, Wood is combining the tradition of late-night oyster barbecues with the ancient pottery furnaces.

Known as dragon kilns, they were built into the hillside so that the released heat would travel upwards. They will be reincarnated as open barbecue pits, roasting everything from oysters, to whole pigs, to chicken, meat and seafood to make paellas.

Developers hope to serve 700 people twice a day, once at 10pm, the other at midnight.

Marriage ceremonies and celebrations are another custom. Residents have converted a few old houses into "marriage houses" where couples go to celebrate after the wedding ceremony at the temple.

Wood intends to enhance and modernize these places, making them fashionable wedding destinations, replete with nearby dragon kiln barbecue banquets. In his vision, couples and close relatives can stay at the marriage houses, while relatives and friends check in to hotels that are part of the project.

This time around, Wood is conscious of the need to attract more locals to the development. In Shanghai, the prices at Xintiandi exclude most locals and foreigners abound. But as Chinese income rises, Wood is optimistic the proportion of Chinese to foreign customers at his developments will change.

"I believe in the evolution of culture. Places like Shanghai Xintiandi play an important role - they have an impact that is a lot more than just commercial. They're part of feeling Shanghainese," he says.

(Shanghai Daily March 16, 2009)