Peerless water city

Hangzhou, the scenic capital of Zhejiang Province, encompasses all sorts of water bodies: sea (East China Sea), lake (West Lake), river (Qiantang), brook (Xi'xi) and canal (Grand Canal). Bountiful water resources grace its land and shapes local culture and customs, bringing its people both blessings and scourges.

The Blessings

It is easy to see the benefits water has brought to Hangzhou. Its West Lake has long been deemed a gem of southern China, its subtle beauty earning Hangzhou the moniker "paradise on earth." Dong Yukun, a 74-year-old native, has been to many parts of the nation, including Taiwan, and has reached the conclusion from these travels that "the West Lake is peerless." Life is never boring in Hangzhou, even for retirees like him. Mr. Dong strolls around the eco-park near his home everyday, from time to time spending hours by the shores of the West Lake, watching the willows and rippling water while sipping tea, or at other times taking a jaunt to the Xi'xi National Wetland Park.

The wetland sprawls across the western section of Hangzhou, five kilometers from the West Lake. There are few wetlands in the world found within urban areas and Xi'xi is one of them. Six rivulets traverse the region, submerging 70 percent of its surface.

The Qiantang River, the largest in the province, draws tens of thousands of tourists every year for its awe-inspiring billowy tides, which gallop with astounding speed and a deafening roar. Hangzhou is the destination of the Grand Canal, which dates back to the Spring and Autumn Period ((770-476 B.C) and extended to its current reaches during the Sui (581-618) Yuan (1271-1368) dynasties. The only direct waterway between Beijing and Hangzhou, the canal served as the cardinal channel between southern and northern China, facilitating trade and exchanges.

The Scourges

With a low altitude and plenty of rainfall, Hangzhou is traditionally prone to floods. Xiao Qiong, a professor who moved to the city in 2005, could hardly believe it when told by her colleagues that a couple of years ago a heavy rain flooded the warehouse of a store on the campus. Goods of all kinds floated around the place, and staff members had to paddle in and out of the shop to chase them down.

Older residents of the city are no strangers to such scenarios. "I have been here for more than two decades. I remember in past years whenever there was a heavy rain almost every family in the old districts had to fight with the water gushing into their homes. Sometimes the water could rise to the height of the bed or above," recalled Zhou Gang, chief architect of the Hangzhou Pavilion at the Shanghai Expo, and deputy dean of the School of Design of China Academy of Art. Zhou believes the root of the problem is not the excess of rain, but urban construction that blocks natural spillways. "Though we replaced them with a greater number of culverts, we didn't see a faster discharge when the flow reached high volumes."

With the fast growth of industrialization and urbanization in recent years, water pollution has become a grim threat to local environment and public health, provoking revaluation of the relationship between economic development and people's well-being.

Harnessing Five Waters

Alarmed by the degradation of water quality and constant menace of flood, Hangzhou began to work on its water system in a holistic manner, protecting water sources, prohibiting waste discharge, dredging silt and connecting rivers and lakes to enable circulation between them.

Water in the higher ends of the city is diverted to the lower western part. While running over this distance it is naturally purified. Meanwhile biological methods are introduced to improve water quality and the aquatic environment. Heavy-polluting fuels are prohibited, and no-aquaculture zones have been set up along major rivers. Some factories were relocated, modern sewage farms were built, and waste emissions were closely monitored.

These measures soon paid off. The water surface of the West Lake expanded, and its water, now renewed every month, resumed its crystal hue. The Xi'xi Wetland reported greater bio-diversity. Live water from the Qiantang River is diverted into the Grand Canal, flushing pollutants and silts accumulated for decades, bringing life back into the once dead water. To accommodate increasing number of visitors to the two rivers, two sightseeing corridors and footways have been built on the bank.

On his tour to the Hangzhou Pavilion at the Shanghai Expo Chen Dusheng, a student of Zhejiang University, wrote on the comment board: "I grew up in a waterfront town. In my childhood I fell in sleep to the sirens of passing ships every night. Water is part of my memory of the old days. Later the river became fouled and the ships fewer and fewer. When I came to Hangzhou and saw the Grand Canal, I was impressed that an ancient canal could retain its shipping life in modern times and meanwhile be so beautiful. My affection for river is awakened again."

|

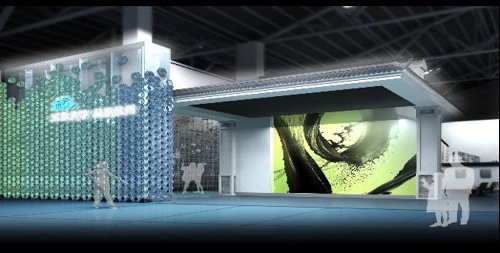

| Hangzhou Pavilion at Shanghai World Expo |

Centuries ago Italian traveler Marco Polo (1254-1324) wrote that Hangzhou is "without doubt the finest and most splendid city in the world." This compliment would be well founded today. As the economy grows at unprecedented speed and human activities make unexpected changes to the landscape, Hangzhou preserves its traditional cordiality with nature, particularly with water, the defining quality of its grace.

0

0

Go to Forum >>0 Comments