Qing Dynasty (1644-1911), emperors would summon top craftsmen from around the country to the Forbidden City and employ them to produce the finest handicrafts in the land.

From exquisite cloisonne vases to delicate jewel boxes, the royal family collected only the very best items, which were out of reach and never seen by ordinary people.

Today, the Forbidden City's walls no longer are barriers to these gems, which can be seen at the Chinese Art Treasures Museum.

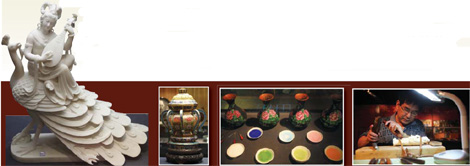

On show are fine examples of Beijing embroidery, palace carpets, inlaid gold lacquer, jade carving, cloisonn, ivory sculpture, gold filigree lacquer ware, and carved lacquer ware.

And the workmanship, which was once passed down from generation to generation, is now becoming an open secret.

The ivory sculpture display occupies a broad space in the exhibition and was the most favored craft by the royals because ivory sculpture always served as a tribute to the emperor.

In the past, the designs of ivory sculpture were usually of the elderly, Buddhist statues, and legendary heroes. Today, younger carvers are making rounded, relief and hollowed and group sculptures.

Li Yunfang, a 48-year-old demonstrator from Beijing Ivory Carving Factory, was carving a 20-cm-long ancient figure. His electric carving tool whirs over the milky surface of the figure, as he whittles away.

"It takes an apprentice at least eight years to master the carving skills, but decades to become an expert," Li says.

Li has been working in the factory for 30 years and witnessed the waxing and waning of the ivory carving industry.

The worldwide ban on ivory trade in 1989 halted poaching, but dealt a heavy blow to ivory craftsmen.

The factory had to rely on less than three tons of ivory left from stocks and earned only 300,000 yuan per year.

The number of workers plummeted from 800 in 1972 to a mere 80 and it was Beijing Arts and Crafts Corporation that saved the factory.

Its revival started in 1996 when China included ivory carving in its first intangible cultural heritage list.

Beijing's government also gave grants of 3 million yuan ($439,155) a year to rescue traditional handicrafts on the verge of disappearance.

Each apprentice of a master recognized by the government receives a 800 yuan ($117) month subsidy.

Traditionalists often mourn how ancient handicrafts are dying out, and the time-honored profession holds no charm for beginners, but the veteran carver views it differently.

"It would worry me for a long time, but the situation is turning better as six newly recruited graduates with a major in painting and designing join us this year," he says.

"Their hard training lets me see a bright future of ivory sculpture. "

At the northern corner of the hall, Cheng Shumei, Beijing's most advanced inlaid gold filigree lacquer artist, is at work.

Cheng is happily passing her beloved profession on to her 36-year-old son and daughter-in-law.

Their latest gilded craft Tai Ping You Xiang (pictured left), a bottle on the back of an elephant, which indicates peace and auspiciousness, attracts groups of visitors.

Filigree and inlaying is a fine craftwork with a long tradition.

The worker braids gold or silver wires into the base and chisels patterns on it, before inlaying pearls and gems.

In the Qing Dynasty, royal lacquer ware workshops made carriages, boats, palanquins, noble-wares, household furniture, utensils, apparatus, as well as various decorations and ornaments for the royalty and nobles.

"Beijing Filigree Factory failed to adapt to the change in fiercer competition in 1990 and eventually bankrupted," says the 63-year-old, who now instructs her successors in her 50-sq-m workshop in a basement of a residential area in Chaoyang district.

Each year, they receive orders from temples and stores selling Buddhist figurines. But the master feels the filigree industry has a dim future.

"My son hasn't mastered all the techniques of the art though he has learned for nearly 10 years. What if his child refuses to take over the workmanship?" she wonders.

Beside a demonstration by Beijing masters, more than 2,500 pieces of ethic artworks are on the show.

9 am-5 pm, until Sept 18. Free entrance. 24 Jinyuchi, Chongwen district, 5217-1111. 崇文区金鱼池中区24号

(China Daily September 9, 2009)