Snow, sunset and Simatai

"To Simatai? Again? Isn't it snowing in Beijing?"

That was my mother on the phone from Calcutta.

I told her that the idea, in fact, was to capture the snow on the ramparts of the Great Wall. Simatai happens to be the steepest, highest (about 1,000 m above sea level) and arguably the most picturesque and least-frequented part of the Wall around Beijing. Built in 1368 and re-built in the mid-Ming Dynasty in the late 16th century, it is also one of the most ancient and unspoilt pieces of the great bulwark. Now was the time to see its virginal brilliance, before the snow melted.

"You'd better watch your step," she said. "The wall's rather ancient, isn't it? Never know when a chunk might loosen and fall off."

|

|

|

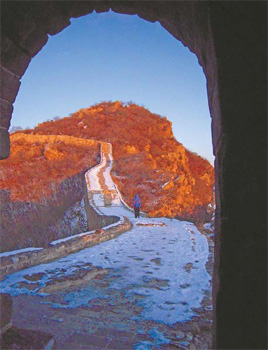

The snow-covered Great Wall is glazed by the rays of sunset. |

My mother can be funny sometimes. But at 6:30 pm, walking down the never-ending snow-caked steps in pitch darkness, as a strong wind threatened to scoop me off the wall and hurl me down the precipitous gorge - right into what seemed at that hour to be the other side of civilization - I thought of my mother.

At sub-zero temperature my hands hung limp, ready to be preserved cryogenically for the benefit of humanity. A thin dribble of phlegm ran non-stop down my nostrils, dripping into the scarf wound twice around my neck and mouth. My legs, under double layers of trousers, were shivering and wobbly. The steps - there must have been thousands of them - were uneven and treacherous, broken and jagged in parts, sometimes eroded to nothingness. The walls on either side, just beneath the parapet, opened up viciously every 2 m or so. They had gaping holes the size of a Cyclop's mouth.

For the first time in my life I wondered if I should start calling out to some of the 330 million gods in the Hindu pantheon. If I slipped and fell on what was now solid blocks of ice, glittering and sparkling under a clear, starlit sky, and broke something and ended up spending the night here, I would surely freeze to death.

But all this happened after a rust - and-crimson sun had gone down behind the dark ridges covered with coniferous trees, toward the west, beyond the lake into which hot and cold springs pour in all the year round, its waters never freezing. My companions, armed with a sophisticated camera, tripod and several combinations of lenses, parked themselves at three of the 15 watchtowers on the east wing of Simatai, keen not to lose a moment of the sun's chiaroscuro effect on the 60 million cubic meters of stone and brick.

I decided to walk up as far as I could, primarily to prevent myself from getting mummified. I passed through the compact, symmetrical arches of the watchtowers, moving eastwards. At each tower I would stop to catch my breath behind the thick walls. I would look out of the arched windows, now glazed by the rays of the setting sun, to watch the molten gold coating the snow-covered slopes beneath like cheese spread.

Once or twice I caught myself leaning too heavily on the windowsill and stepped back with a start. The wall had crumbled in places, enlarging the windows or doing away with them altogether. When I reached the Fairy Maiden Tower, the place where a sign read "no couching", I decided I would rest there for a while. The very desolate nature of this crumbling tower, pushed to the eastern fringe of the hills, was inviting.

Sitting in its doorway, with the expansive landscape of hills, trees, lake and the rise and fall of the Wall, like a melody, spreading out in front of me was like having a seat in the dress circle, watching the sun bowing out for the day, dressed in full regalia.

The paved road of the wall seemed to end here. But another one, so narrow that it was almost invisible in parts, which rose from a blocked wall of the tower, shot off toward the peak, leading to the eponymously called Watching Beijing Tower. My friend Gao Yansong scrambled up the broken footpath to catch a view of Beijing by sunset and record it on his camera, but I chose to stay put with the fairies, ears pressed against the wall, listening for sounds of music and laughter.

Soon the sun would go down behind the hills, touching everything on its way - the bare trees growing on the slopes, the icy serpentine stretches of the Wall running like a series of wide parabolic curves in sync with the rise and fall of the ridges, the Heavenly Ladder, almost a 90-degree gradient, rising up the craggy knoll, resembling a crooked cottage with a chimney.

After dark, when the visitors have all gone home, Simatai stands alone, listening to the sound of springs - one hot and the other cold - pouring into a lake that never freezes.

0 Comments

0 Comments

Comments