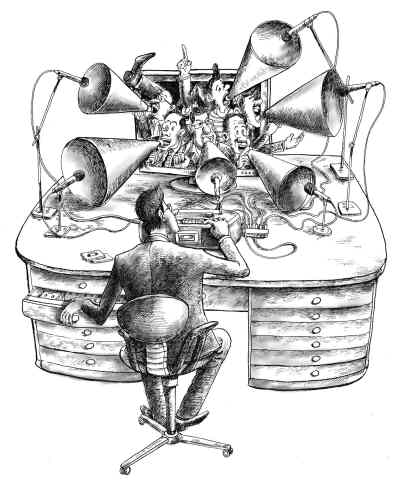

A freedom of speech with Chinese characteristics

- By Xu Peixi

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail

China.org.cn, August 5, 2011

E-mail

China.org.cn, August 5, 2011

|

|

[Peolpe.com.cn] |

Freedom of expression in China never fails to fascinate global readers. To gain a reasonable understanding of a current situation, one needs to know about the distance from two extremities. That is, the degree of speech freedom in China can be judged neither by the quantitative data provided by Chinese officialdom to argue for a level of sufficiency, quoting often the number of newspapers, TV outlets, websites, and uploaded posts, among others, nor by the existence of a so-called great fire wall or search engine results on certain words on the lips of some foreign journalists, occasional visitors, or politicians to claim that freedom of expression is systematically absent.

Government officials are dependent on dizzying numbers of growth to illustrate the progress of speech freedom in China. They repeat statistics that China has more than 660 million radio listeners, more than 1 billion TV viewers, an average daily newspaper circulation of more than 100 million, nearly 500 million Internet users, nearly 900 million mobile phone users, each the largest in scale in the world. As early as 2003, Liu Binjie, head of the General Administration of Press and Publication, used these numbers to conclude that "China is one of the countries in the world enjoying the most sufficient degree of freedom of expression and publication."

Official documents reveal the same logic of looking at freedom of expression through the lens of quantitative increases. For instance, China's official white paper on the Internet, published in 2010, claimed that "Chinese citizens fully enjoy freedom of speech on the Internet" by referring to the fact that 80 percent of Chinese websites provide an electronic bulletin service, that China has 1 million of these BBSs and 220 million bloggers, and that 66 percent of Chinese netizens "frequently" post online. The white paper regarded the "vigorous online exchange" as "a major characteristic of China's Internet development." But in essence, this may well be a reflection that freedom of expression is badly guaranteed in offline settings. The newly-released Assessment Report on the National Human Rights Action Plan of China (2009-2010) embodied the same logic by enumerating a similar set of numbers on people's right to express.

This kind of treatment for speech freedom is a projection of Chinese officials' mentality on handling social concerns from an economic perspective. According to Roberto Savio, founder of Inter Press Service, this mentality is typical for a developing state. Many countries in the global South have a tradition of prioritizing quantity over quality when dealing with information issues. But a quantitative framework is insufficient. Figures of this type, at its best, can only be read as better preconditions for the improvement of freedom of expression. A more cautious articulation of freedom of expression should take into consideration not only facilitating access to media by delivering infrastructure services, which the Chinese administration is extremely good at, but also executing this Constitutional right by reforming legal and administrative mechanisms in practice.

Other people swing to another extreme about speech freedom in China. A regular piece of evidence favored by Westerners is China's blocking of popular Western websites such as Facebook, YouTube and Twitter. In his Shanghai Town Hall speech in 2009, U.S. President Barack Obama responded to a question about Twitter that the U.S. has "free Internet," namely, "unrestricted Internet access." But he never mentioned that such a version of freedom is largely market-coordinated in nature and that the U.S. was planning to militarize the Internet through its cyber war guidelines. Frustrations with Julian Assange and Aaron Swartz, founder and director of Demand Progress, revealed a revival of old problems with a U.S. vision of speech freedom mixed with military solutions and commercial interests.

The EU position essentially differs from the American concept in that there has been a strong impetus to guard against the misuse of freedom for appeals of war, a lesson learned from two devastating world wars on the continent. But when talking about human rights matters in China, EU officials give an impression of betraying both their home position and a critical, philosophical European tradition and share the same conception of the negative freedom of the media. Commenting on the role of French media in diplomatic disputes caused by a disrupted 2008 Beijing Olympic torch relay in Paris, French Ambassador Hervé Ladsous proudly claimed that "French press is free and absolutely free," as if he thought Chinese don't read works of French thinkers such as Michel Foucault.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)