China-the world's financial superpower

There is an interesting game called 'when will China overtake the US to become the world's largest economy'?Mechanical projection of existing growth rates gives the answer 2018. Goldman Sachs, arguing that some slowing of China's economy will take place, gives the answer 2026.

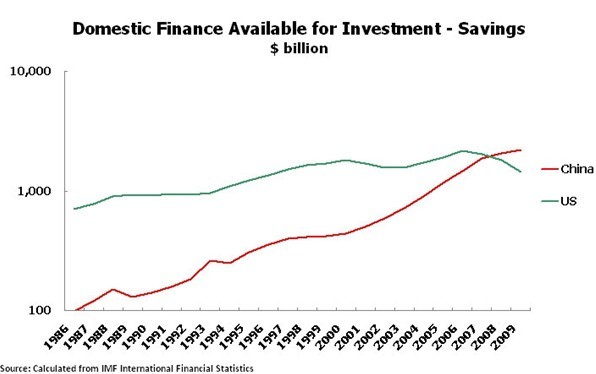

What is not generally realised is that China passed a decisive financial landmark this year when it overtook the US as the world's largest generator of finance available for investment. As China has overturned a lead that the US has enjoyed for a century and a half, this may be termed, without exaggeration, a turning point in world financial history.

To set out the data starkly, the official US Bureau of Economic Analysis measured combined US company, government, and domestic savings in the second quarter of 2009-the latest available figures-at an annualised $1.4 trillion.

China does not publish quarterly savings figures, but it is relatively easy to calculate them from other published data. At official exchange rates, which understate the real size of China's economy, China's finance available for investment, that is savings, reached an annualised $2 trillion in the second quarter of 2009. This more than $600 billion lead over the US is sufficiently large that, even allowing for a generous margin of error given the indirect way China's figures must be calculated (aggregating fixed investment, inventories, and the balance of payments surplus), there is no doubt that China has now overtaken the US as the world's greatest domestic generator of capital.

A lead the US has enjoyed over every competitor since it passed Britain to become the world's largest economy in the 19th century has disappeared. That is why it may be legitimately said that a new era in world finance has begun.

Two processes explain why the shift took place this year. As can be seen from Figure 1 China had been closing the gap with the US for many years. However, purely on previous trends, it would have taken China the better part of a decade to overtake the US.

The new factor was the damage done to the internal structure of the US economy by the international financial crisis. Just as when the iceberg struck the Titanic–the damage caused was worse below the waterline than above it.

The visible damage from the financial crisis is the US recession and rising unemployment. The damage below the waterline, from which it will be much harder to recover, is the extraordinary fall in the already low US savings rate-in other words, the ability of the US to generate domestic capital.

Total US savings, at annualised rates, have fallen from their peak of $2.2 trillion dollars in the third quarter of 2006 to $1.4 trillion. Expressed as a percentage of GDP the drop is from 16.2 percent to 10.2 percent. The latter figure is the lowest since 1934. US savings have therefore fallen to levels last seen in the midst of the Great Depression.

Equally striking, the level of US investment (14.7 percent of GDP) is scarcely above its calculated rate of capital consumption (12.9 percent of GDP)–which means that, in net terms, the US is scarcely accumulating capital.

Such an extraordinarily low investment rate precludes a rapid rate of recovery from the economic downturn. US economic growth following the recession will therefore be relatively anaemic compared to previous downturns. China will meet its 8 percent GDP growth target for this year and is likely to see still higher growth in 2010–cutting the gap between the size of the Chinese and US economies by around a trillion dollars in 2009-2010 alone.

None of this, of course, means that China is about to eclipse the US. Even when China's economy becomes as large as that of the US, it will still only have reached one quarter of the GDP per capita. And China's overall institutional economic strength–as measured by the size of its companies, the proportion of its economy devoted to research and development, the organisation of its markets, its ability to handle very high value production, its ability to run companies abroad–still remains considerably weaker than that of the US. One of the great merits of China's economic leadership is that it does not conceal such facts and engage in self-delusional braggadocio, but openly addresses them.

But all these necessary skills can be acquired with time and effort. China's underlying financial strength means it is well able to sustain its leading companies as they move up to world standards. The first international efforts of what are now world-beating firms from Japan and South Korea, such as Toyota and Samsung, were far more primitive than those of present Chinese companies such as Haier, Hisense, or Chery.

Such underlying financial strength also gave China the ability to launch its stimulus package–the speed and decisiveness of which enabled China to achieve its 8 percent growth rate target. Financial strength will also allow the inevitable rough edges of such a huge package to be overcome. And that is why those who point to this or that inevitable individual problem have really lost the main plot. No country in the world could deliver a program on such a scale without encountering problems in some areas, as well as greater than expected successes in others. China's underlying financial strength allows any particular problems, such as some inevitable rise in bad loans, given the huge expansion of lending, to be mopped up with the resources generated by rapid economic growth. This is why the problems connected with China's stimulus package have been far less than those seen in the US.

Finally China's underlying financial strength is why, in the international debate on China's economic stimulus package, those who have been predicting failure, such as Stephen Roach of Morgan Stanley or Michael Pettis of Peking University, have been consistently proved wrong by the unfolding economic data, while the views of those who have been predicting success, such as Professor Danny Quah of the London School of Economics, the present author, or Jim O'Neill of Goldman Sachs have been vindicated by events.

In China it is always necessary to see the big picture.

|

0 Comments

0 Comments

Comments