"Learning another cuisine is like learning another language. When you learn a language, you learn the grammar and examples to reproduce and make up the sentences. I learned the basic processes: the art of cutting, how to make the flavors, the art of the wok, controlling the fire. Once you learn the patterns of the cuisine, you can start being creative and play around with the basic grammar," she says.

Key to Dunlop's success, both as an adventurous eater and a culinary scholar, was a curiosity born of being an outsider. Dunlop is fluent in Mandarin and steeped in Chinese culinary cultures, yet her own background is completely different, giving her a critical distance that allows her to bridge Chinese and British cuisines and traditions.

She is also able to bring to her books an ability to make Chinese cuisine more accessible to English-speaking audiences who are unfamiliar with Sichuan spices or the textures of offal.

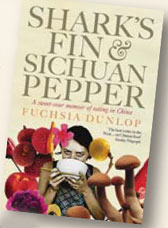

Shark's Fin and Sichuan Pepper ends on an interesting note on the gourmand's place in a world where the local and organic movements are gaining momentum and the global supply of food animals is rapidly being depleted.

After eating her way through everything, Dunlop has very few taboos left, other than one that is crucial: endangered species. For instance, although the shark's fin of her book's title is popularly feted as a traditional Chinese delicacy, Dunlop won't eat it again.

But just as eating in China raises questions for Dunlop, she also finds in Chinese cuisine some of the answers that have been there all along.

Dunlop sees in China's traditional meals of vegetables with a small amount of meat, tofu, and rice, "a model for the entire human race" because it has "minimal environmental impact, is nutritionally balanced, and marvelously satisfying to the senses."

"There's a great pleasure in eating modestly and ethically," she observes, "and we'll all have to learn how to do it."

(China Daily June 3, 2008)