If the main dishes during your Christmas Eve dinner feature

vegetables - mushroom soup, baked cod or dried fruit - chances are

you're either from Russia, hanging out with a Russian family or you

came from a country in which Orthodox Christians observe Christmas

today.

Either way, Christmas for Russians and other members of the

Orthodox Church comes 13 days after the widely observed date of

December 25. But the significance and history of this day remain

the same for most people around the world.

The January 7 date is based on the Julian Calendar named after

Julius Caesar who introduced it in 45 BC.

Some people observe both the mainstream December 25 date and the

Orthodox Christmas. Squeeze New Year's in between, and it means

that some people halt work for up to three weeks to enjoy the

festive season with friends and family, says Russian Yury Ilyakhin,

who now runs an Internet-based company in Beijing.

"In Russia, a lot of people celebrate these three events. Nobody

in Russia works at this time; it's very difficult to find people,

but it's different in China," the 52-year-old says. Since his

employees are all Chinese, Christmas is a working day.

"Chinese people don't celebrate Christmas, and of course they

don't know anything about Russian Christmas," Ilyakhin says.

When work wraps up today, he plans to join his wife and friends

for dinner at a Russian restaurant.

"This is not a noisy celebration; it's a very quiet one," he

says. "We love this holiday, because the air is clean and the snow

is white."

Although many Orthodox Christians in China may not feel the same

holiday spirit as they did back home, they cherish chances to spend

time in local Russian restaurants or in the company of good

friends.

Serbian Marija Lucic, 27, who now works as a sales manager at

the Grand Hyatt Hotel in Beijing, recalls her childhood

Christmastimes back home.

"It's an excellent opportunity to get the whole family

together," she says.

In Serbia, she says, the holiday meant a gathering with her

mother, father and siblings. She says it's traditional for many

people to buy a tree - not the Tannenbaum varieties, but rather, a

yellowish dried tree.

"We bring it into the house a couple of days before Christmas

Eve and it's important that a man brings this into the house, based

on tradition," Lucic says.

Orthodox Christians usually dine exclusively on vegetarian meals

- free of animal fat and oil, in addition to meat - for the 40 days

leading up to January 7. However, fish is fine in the lead-up to

the big day, after which meat becomes a dietary staple.

"After 40 days of constraining themselves, they eat all the

worst things - pork with a lot of pork oil, sour cabbage with

minced meat inside, and this is a very traditional kind of meal on

Christmas Eve or Christmas night," Lucic says.

Unlike traditional Western Christmas, Orthodox Christians in

Serbia prepare rounded bread instead of cakes.

She expects to spend the festival with friends in Beijing.

"I have a lot of foreign friends in Beijing, and I join them,"

she says. She also plans to visit her best friend's family to

celebrate the day with a dinner.

Ilyakhin says a recent chat with Russian fans flooded his mind

with memories of Russian Christmastime, called Rozhdestvo in

Russian.

"For those of us who strictly follow the religious tradition,

the most important (thing) is to keep the fast for four weeks," he

says. "The day before Rozhdestvo is called Sochelnik. It came from

the word associated with water, because on this day, one should eat

grain with water - gruel, boiled rice, boiled buckwheat, millet

porridge - sometimes with honey. We call this meal kut'ya in

Russian."

He explains it's also a fun opportunity for young people in

Russia to dress up.

"In the evening, children went to the neighborhood for kolyadki

(singing songs and asking for gifts) - wearing some frightening

clothes, pretending to be a bear, goat or wolf, like young people

now love to do on Halloween," Ilyakhin says. "They sang Christmas

songs and asked for sweets."

Many people also join their families at church to pray, and some

even stay for the entire night to pray and sing, he says. "In

Beijing, unfortunately, we have no Russian Orthodox church, so many

people go on this night to the embassy," he says.

He says the service at the embassy's church attract people from

many countries: Russian, Ukraine, Belorussia, Armenia, Georgia,

Serbia and Slovakia.

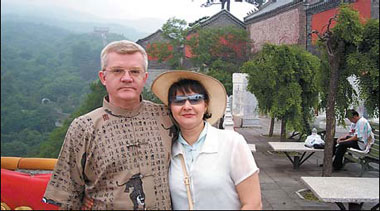

For Ilyakhin and his wife, Katya Ilyakhina, Beijing isn't just a

place to make a living. His wife is a conductor of a music choir,

and he runs a business. He was recently selected as a torchbearer

during the Beijing Olympics.

He says that being so far away from Russia perhaps makes the

holiday extra special. And he says small reminders such as a photo

on a table helps to remind him of his former home.

Ilyakhin also notes that in Russia, even the January 7 Christmas

was banned for decades. It began soon after the 1917 Revolution,

and it was not until 1992 that Russians could openly observe the

holiday or attend church services without fear.

Today, most people enjoy the holiday freely by visiting churches

and gathering with family and friends.

But for Ilyakhin, not all of his boyhood memories of the season

are positive. He remembers that when he was in school, he and other

students were instructed to visit at least one church to report

back how many people were inside the church - a tactic intended to

discourage people from worshipping.

But those days are in the past. And now, he's in Beijing to

celebrate the holiday. "Maybe it will be snowing on January 7 in

Beijing, and I would like it very much," he says.

(China Daily January 7, 2008)