Before the 1990s, Basha (岜沙) was a small village almost unknown to the rest of the world. Perched on a hill about 7 km away from the central town of Congjiang County, in Southwest China's Guizhou Province, the village is home to around 470 households and 2,200 Miao ethnic people, who had been leading a life that was virtually untouched by modernization.

They grew rice in the mountains and fed poultry at home. They lived in wooden stilted houses and built rafts to dry un-husked rice. In their spare time, men hunted, and women stayed at home weaving cloth and making shoes.

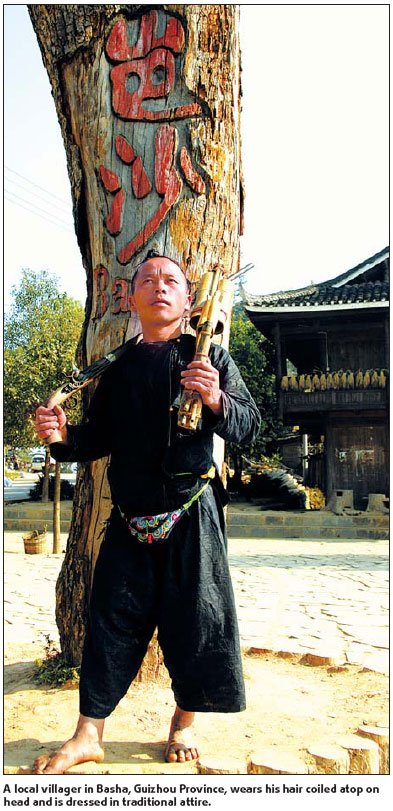

They wore traditional attire and grew their hair long. Even men, with the brims of their heads shaved with a sickle, grew their hair long enough in the center to be coiled atop of their heads.

They worshipped trees in a way that most others would worship their ancestors. They married people from the same village or those in close vicinity, and most of them had never even been to the central town of Congjiang County, even though it was only 7 km away.

Life remained peaceful until the late 1980s. Then came television, which drew the village towards modernization, according to Jia Yunliang, the chief of Basha. Jia still recalls his first visit to the central town of Congjiang. While he was surprised by the new things he saw there, Jia was ridiculed by the locals.

Drawn to the outside world, Jia, along with many of his peers, blamed their "strange, outdated" and even "stupid" traditions, Jia recalls. To avoid being mocked, he would wear a hat and modern clothes to hide his ethnic identity whenever he went outside of the village.

When he turned 15, the age when villagers can decide to keep their hair long or shave it off, Jia happily chose the latter. However, 10 years later, Jia grew his hair long again and became an advocate for the preservation of local indigenous culture.

Over the years, the customs Jia was once so eager to shake off have caused Basha to progress from a little known village to one of the most visited places in Guizhou.

First discovered by photographers in the mid-1990s, Basha soon after became a popular destination for backpackers. Dubbed as "the living fossil of Miao's ethnic culture", it has been rated as one of the "Top Ten Tourist Destinations for Chinese Singles".

The number of visitors has increased from a few hundred each year in mid-1990s to around 40,000 this year alone. Due to the interest in Basha's traditional culture, the village has formed two entertainment groups.

However, even though the village attracts an increasing number of visitors every year, it is still not as commercially successful as Lijiang, a World Heritage site in Yunnan Province. As a result, the morale of Jia and his fellow villagers has waned.

An increasing number of teenagers are dropping out of school to work in big cities, and they return influenced by urban culture which conflicts with their traditions.

Due to the modernization of the village, such as the newly paved main street and the commerciality of the local performances, tourists are spending less time here, according to Zhang, a tourist from Liuzhou in South China's Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region. As an avid photographer, Zhang has visited Basha four times in the past 10 years. But he says his most recent visit earlier this month, would be his last.

Tourism, which once saved Basha's indigenous culture, may now be the factor in its eventual demise.

Over the last decade, Jia has been to most of China's big cities showcasing Basha's traditional customs. One thing he has learned from those experiences is that "the appeal of modernization is almost irresistible".

In fact, what Basha is experiencing can be seen across the globe, with Lijiang being one of the best examples. Tourism poses a great challenge to the conservation of the ecosystem and the heritage of the Naxi ethnic group.

"Tourists may be the problem, but the solution lies with the locals," says Han Qunli, an adviser on UNESCO's Man and Biosphere program in Southeast Asia.

In a recent regional seminar jointly hosted by the Eco-tone Southeast Asian Biosphere Reserve Network and the Chinese Biosphere National Committee, Han, along with some 200 experts, managers and community representatives, agreed that the protection of indigenous culture is at the very foundation of sustainable development.

"One thing we have to be careful about is that by cultural diversity, we don't restrict it to folklore and cultural expressions," Han says.

"Rather, it consists of a deeper philosophy that has enabled many of the indigenous ethnic people to maintain a harmony between human beings and nature.

"Once we've got the essence of the indigenous culture and keep it alive, a sustainable use of cultural and biological resources can be expected."

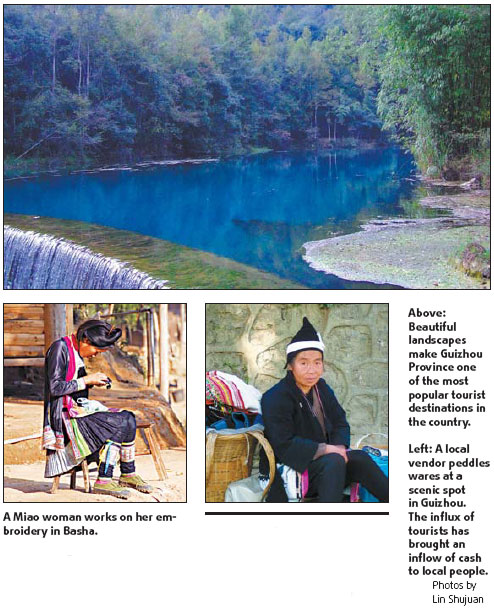

Compared to neighboring Yunnan and Guangxi, Guizhou has been lagging in tourism development over the last decade, despite the fact that the province boasts breathtaking landscapes and is rich in ethnic culture.

However, in recent years as Yunnan and Guangxi have allegedly become too commercial, tourists are now increasingly traveling to Guizhou for a more authentic sampling of ethnic culture.

The recent addition of Guizhou's Libo Karst to the World Natural Heritage List is also expected to promote the growth of the province's tourism industry.

"We've been thankful that our traditional respect for nature has left with us a mosaic of culture, green mountains and clear water," says provincial governor Lin Shusen.

"While we're counting on tourism for a higher quality of life, it is our responsibility to maintain what we have in our ecosystem, or in some cases, restore it to its former splendor."

(China Daily by Lin Shujuan November 27, 2007)