History buffs may not be entirely amazed at the vast remakes in and around the 100,000-sq-m Yangguan Museum, but few can imagine Yangguan without it.

Before the museum opened four years ago, there was nothing in the area but ruins, barren on the arid floor of the Gobi Desert. The relics were spread apart, miles away from each other. Some were hidden in the middle of the desert, and others were not even accessible to the public. By the end of the day, a visitor would be left with little more than disappointment, frustration and a pricy cab fare.

Some preservationists may be skeptical of the museum, preferring to spend time exploring the wild in its natural state. It's easy, to point fingers at the museum and criticize its fake renditions. But all the haters should remember this: the museum is built and operated by a true history buff, with money out of his own pocket.

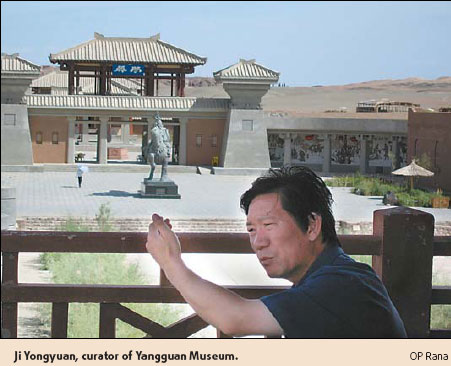

Say hello to 52-year-old Ji Yongyuan, who wasn't exactly born to be a historic preservation expert. In fact, after years dedicated to the museum's cause, he still doesn't regard himself as any kind of historian.

Considering the fact that he has spent most of his life studying art, the argument against his credentials as a historian does hold some validity. Ji, a Dunhuang native, studied traditional Chinese painting in Tianjin Municipality and spent years learning about the Mogao paintings in particular. In 1983, he established the Dunhuang Art Academy to "explore the combination of art and business through an avenue of cultural development without state funds".

As the 1980s unfolded, his success escalated as the academy grew and he established an artists' association. In 1990, Ji set up the Dunhuang Institute, a part of a Chinese art correspondence college. Over the next few years, he and eight professors toured the Far East with 154 students and their art. They appeared in various road shows in Japan, South Korea and China's Taiwan and Hong Kong, earning both fame and fortune.

Ji put virtually all the money he made in those 20 years into the Yangguan Museum. He began building in 1999 with 18 million yuan ($2.4 million) of his own money, another 10 million yuan loan from a bank, and a 9 million yuan subsidy from the government.

"My interest slowly shifted to Yangguan since my first trip in 1991," he said. "Unlike the Grottoes, the protection, promotion and utilization of the Two Passes was exceptionally terrible. Visitors all came with high hopes and left in utter disappointment. The ones who came were as sorry as the ones who didn't."

"I hope our museum can be of use in the preservation and promotion of our relics, and in boosting the local tourism industry," he said.

With over 4,000 relics on display and 2,800 others due to greet tourists soon, Ji's museum is already one of the best in the field. But still, Ji isn't too impressed.

Ji said that total investment in the museum should be around 68 million yuan, but he has only managed to account for half of that. In fact, the museum is struggling to break even. In addition to the annual interest Ji pays the bank (almost 700,000 yuan), he has to feed 76 employees (most of whom are under 30) and train interns in local universities, gather more relics, and develop the local tourist district.

But business at the museum is booming. The museum hosted 20,000 visitors when it opened in 2003 and roughly 60,000 are expected this year. If the number reaches 100,000 by 2010, the museum will see a profit of eight to 10 million yuan per year, more than 2 million of which will be spent on research and development.

That time hasn't come yet, but Ji is happy enough with the fact that he's right where he is supposed to be. "People who run museums are all idealists," he said. "Doing something like this has always been my dream. Now, that dream has been realized."

(China Daily September 27, 2007)