It is a little surprising to see the tourism scene flourishing in Zhaoxing, a small town located at the joint area of southwest China's Guizhou Province, central China's Hunan Province and south China's Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region.

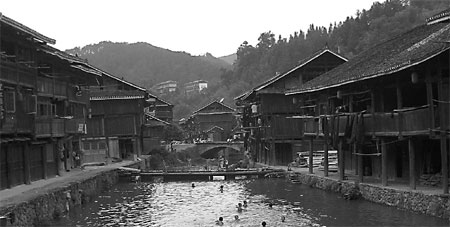

The river running through the town of Zhaoxing determines the pulse of local people's lives.

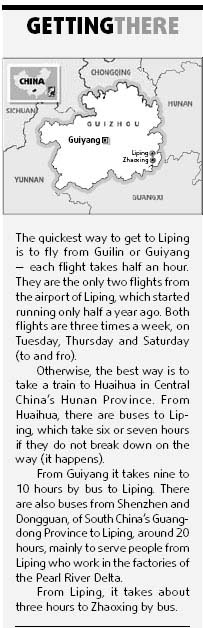

A subordinate township of the Liping County of Guizhou, it's a long way from any major city. I had spent nine hours on a bus from Guizhou's capital city Guiyang to Liping, and then another two hours in a car to Zhaoxing.

Most tourists seemed to have flown from Guangxi's Guilin to Liping, while the backpackers may have come from any of the three regions. Though hard to get to, the joint area of Guizhou, Hunan and Guangxi, occupied mostly by the Dong ethnic group, has preserved some of the most original natural beauty and cultural traditions in China.

Travelers from other countries can be seen from time to time in Zhaoxing. As a result, signs in English are ubiquitous, though it often takes some thinking before you can understand the meanings of those signs.

For example, "The Race Gathers the Ancient Handicraft Product Store" means "Ethnic and Ancient Handicraft Store", while "Chiyu Motorcycle the Appliance Maintain the Store" means "Chiyu Motorcycles and Electric Appliances Maintenance Store". You are also welcomed to stay at a hotel room with "televiolon" and "hot baht".

Unlike some places where everything has been made to cater to tourists, it seems that in Zhaoxing the local culture lives harmoniously with tourism. On one side of the town are hostels and bars packed with tourists, while on the other side is a river where local Dong people wash their rice and clothes, as well as themselves and their cattle.

You will learn much about the Dong culture by watching local people's activities, as long as you can stand the sight of ducks being slaughtered in the street and dogs' heads sold along with pork at the market.

For dinner, my local friend Xiao Li invited me to a restaurant with "race taste". At the restaurant, I found that we would have a hotpot with niubie. I had heard about niubie when I was in Liping. From my understanding, it is the digested grass in a cow's stomach.

"No, that's not the real niubie," said the chef of the restaurant, who allowed me in the kitchen to watch the way he cooked. "The real niubie is taken from the cow's intestine, just before it's too late to eat it."

After putting some garlic and chili into the hot oil, he took out a Coca Cola bottle of niubie from the refrigerator, which he said was from a cow killed that morning, and poured it into his pot. It was a kind of green thick liquid. Then he added some water and a kind of local herb.

Soon, the hotpot was ready and we began to dip all kinds of meat and vegetables in the soup. A lady at our table refused to eat it, for she believed that only niubie served in the morning was fresh.

I tasted the soup, and it wasn't bad. A little bitter, but the aftertaste was nice. Probably, it would have been even better if I didn't know where it came from.

Li said that niubie is very good for the stomach and intestine, and that we could also have yangbie, the equivalent of niubie from a sheep, but I told him that the niubie hotpot was enough for me for the night.

The Dong people have a saying that, "Foods feed the body, while songs feed the soul". When my stomach was full, I felt like having some music.

Luckily for me, a troupe from the Tongdao Dong Autonomous County of Hunan Province was visiting Zhaoxing, and there was a joint performance by them and a local troupe at an outdoor stage that evening. When we got there, the small square before the stage was already packed with people. We had to squeeze into the crowd.

Music has a special place in the Dong people's lives. Without a traditional written language of their own, the Dong people have recorded much of their history and culture in their songs.

The "big song" (da ge in Chinese, ga lao in Dong language) of the Dong people was one of the most special forms of folk music that I have ever heard. It is a kind of a cappella in different parts, sung by a group of singers in bright voices that have been shaped by the unique environment of the area.

My local friends explained the lyrics to me. Some were about nature, while the antiphonal songs were mostly about courtship. Most impressive was the Cicada Song, in which the singers imitated the flickering of cicadas' wings with quick sextuplets.

Choirs of big songs have won many awards at national competitions and have participated in international arts festivals. More and more tourists who come to Zhaoxing want to see them perform, and now travel agencies and hotels in Zhaoxing can arrange concerts.

The performance I saw was good, but I regretted not coming here last spring. They told me that during Spring Festivals, those who went out to work returned home, and married women in their home villages. The Dong people then gathered to sing songs for days, not to perform, but to enjoy themselves.

That night, I checked into a small riverside inn where a double room cost 30 yuan (US$4), with a shared bathroom. Here, I could enjoy a view of the river and the people who lived by it. I felt tired after a day's travel. Listening to the sound of the flowing water, I soon fell asleep.

The next day, I took a walk around Zhaoxing. Like all Dong villages, Zhaoxing is surrounded by mountains, terraces and forests. A river runs through the town.

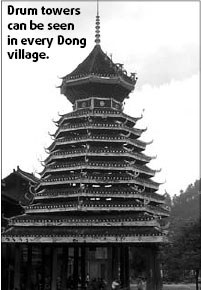

The Dongs are very community-minded. Every Dong community has a drum tower (gu lou), a wind-and-rain bridge (fengyu qiao) and an opera stage (xi tai). The drum tower is a place where people meet to discuss community affairs and sing folk songs. The wind-and-rain bridge is for people to rest and the opera stage is where the Dong operas are put on, usually during festivals.

The town of Zhaoxing was formed on the basis of five clans, which developed into five communities named Ren (benevolence), Yi (justice), Li (propriety), Zhi (wisdom) and Xin (faith). As a result, there are five drum towers, five wind-and-rain bridges and five opera stages in Zhaoxing, making the town richest in traditional Dong architecture.

I decided to spend my last two hours in Zhaoxing idling on the wind-and-rain bridge of the Zhi community, where I met Zhang Gensheng, a 49-year-old primary school teacher.

Zhang told me that tourism has made Zhaoxing a wealthier township in Liping, which is a poor county in southwest China, but some families in Zhaoxing still have hard lives.

Learning that I came from Beijing, Zhang said he had a friend in Beijing named Liu Qingwen. A retired editor of the Legal Daily, Liu had been supporting one of Zhang's students to finish her study through primary school and middle school. Zhang had never met Liu, but they often wrote to each other.

"I had a friend in Beijing, and now I have two," Zhang said to me. "I hope I can go to Beijing to see the two of you some day."

(China Daily September 6, 2007)