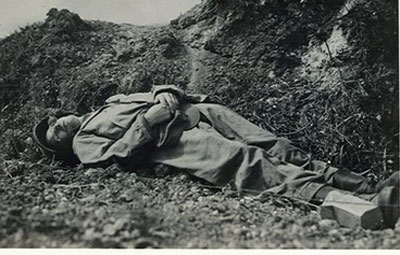

The figure in the photograph is clad in Army fatigues, boots and helmet, lying on his back in peaceful repose, folded hands holding a military cap. Except for a thin trickle of blood from the corner of his mouth, he could be asleep.

But he is not asleep; he is dead. And this is not just another fallen GI; it is Ernie Pyle, the most celebrated war correspondent of World War II.

As far as can be determined, the photograph has never been published. Sixty-three years after Pyle was killed by the Japanese, it has surfaced surprising historians, reminding a forgetful world of a humble correspondent who artfully and ardently told the story of a war from the foxholes.

This photo provided by Richard Strasser, perhaps never before published, shows famed World War II war correspondent Ernie Pyle shortly after he was killed by a Japanese machine gun bullet on the island of Ie Shima on April 18, 1945. Pyle, 44, had just arrived in the Pacific after four years of writing his popular column from European battlefronts. The Army photographer who crawled forward under fire to make this picture later said it was withheld by military officials. An AP survey of history museums and archives found only a few copies in existence, and no trace of the original negative. (photo: Agencies via China Daily)

"It's a striking and painful image, but Ernie Pyle wanted people to see and understand the sacrifices that soldiers had to make, so it's fitting, in a way, that this photo of his own death ... drives home the reality and the finality of that sacrifice," said James E. Tobin, a professor at Miami University of Ohio.

Tobin, author of a 1997 biography, Ernie Pyle's War, and Owen V. Johnson, an Indiana University professor who collects Pyle-related correspondence, said they had never seen the photo. The negative is long lost, and only a few prints are known to exist.

"When I think about the real treasures of American history that we have," says Mark Foynes, director of the Wright Museum of World War II in Wolfeboro, N.H., "this picture is definitely in the ballpark."

Ernie Pyle, war correspondent beloved by his co-workers, GIs and generals alike, was killed by a Japanese machine-gun bullet through his left temple this morning ..."

The news stunned a nation still mourning the death of Franklin D. Roosevelt six days earlier. Callers besieged newspaper switchboards. "Ernie is mourned by the Army," said soldier-artist Bill Mauldin, whose droll, irreverent GI cartoons had made him nearly as famous as Pyle.

He was right; even amid heavy fighting, Pyle's death was a prime topic among the troops.

"If I had not been there to see it, I would have taken with a grain of salt any report that the GI was taking Ernie Pyle's death 'hard,' but that is the only word that best describes the universal reaction out here," Army photographer Alexander Roberts wrote to Lee Miller, a friend of Ernie and his first biographer.

But Ernie Pyle was not just any reporter. He was a household name during World War II and for years afterward. From 1941 until his death, Pyle riveted the nation with personal, straight-from-the-heart tales about hometown soldiers in history's greatest conflict.

In 1944, his columns for Scripps-Howard Newspapers earned a Pulitzer Prize and Hollywood made a movie, Ernie Pyle's Story of G.I. Joe, starring Burgess Meredith as the slender, balding 44-year-old reporter.

Typically self-effacing, Pyle insisted the film include fellow war correspondents playing themselves. But he was killed before it was released.

In April 1945, the one-time Indiana farm boy had just arrived in the Pacific after four years of covering combat in North Africa, Italy and France. With Germany on the verge of surrender, he wanted to see the war to its end, but confided to colleagues that he didn't expect to survive.

At Okinawa he found US forces battling entrenched Japanese defenders while "kamikaze" suicide pilots wreaked carnage on the Allied fleet offshore.

On April 16, the Army's 77th Infantry Division landed on Ie Shima, a small island off Okinawa, to capture an airfield. Although a sideshow to the main battle, it was "warfare in its worst form," photographer Roberts wrote later. "Not one Japanese soldier surrendered, he killed until he was killed."

On the third morning, a jeep carrying Pyle and three officers came under fire from a hidden machine gun. All scrambled for cover in roadside ditches, but when Pyle raised his head, a .30 caliber bullet caught him in the left temple, killing him instantly.

Roberts and two other photographers, including AP's Grant MacDonald, were at a command post 300 yards away when Col. Joseph Coolidge, who had been with Pyle in the jeep, reported what happened.

Roberts went to the scene, and despite continuing enemy fire, crept forward - a "laborious, dirt-eating crawl," he later called it-to record the scene with his Speed Graphic camera. His risky act earned Roberts a Bronze Star medal for valor.

Pyle was first buried among soldiers on Ie Shima. In 1949 his body was moved to the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific at Punchbowl Crater, near Honolulu.

Roberts' photograph, however, was never seen by the public. He told Miller the War Department had withheld it "out of deference" to Ernie's ailing widow, Jerry.

"It was so peaceful a death ... that I felt its reproduction would not be in bad taste," he said, "but there probably would be another school of thought on this."

(Agencies via China Daily February 4, 2008)