Less than 10 years ago, Taikang Road was a typical Shanghai lane community, full of the noise and smells of families living within whispering distance of each other. Housewives haggled over the price of live chickens at outdoor markets; men smoked cigarettes and slapped cards down courtyard tables. Neighbors shared taps, toilets and a sense of the working-class struggle.

In the intervening years, hundreds of similar communities across the city have been torn down to make way for high rises and malls. The brick-lined lanes that radiate off Taikang Road almost fell victim to the same fate. But a coalition of artists, architectural preservationists and city officials fought a successful battle to reverse a decision to send in the bulldozers.

Today Taikang Road "Creative Park" is booming. New galleries, cafes and boutiques are opening like clockwork, and a massive expansion program is under way to fully exploit the thousands of visitors seeking to experience the earthy atmosphere of old Shanghai. Residents are also cashing in on the action, in some cases moving out so they can rent their homes for substantial sums.

"Tianzifang", named after an ancient Chinese artist, seems well on its way to achieving aesthetic and commercial success. The main challenge now, however, is preventing the renaissance from destroying the community's chief charm: its eclectic mix of struggling artists and small businesses surrounded by the ebb and flow of a living community.

The lanes of Tianzifang, located in southwest Luwan District near Xujiahui Road and the North-South Elevated Highway, are chockablock with shikumen (stone-gate) houses built in the 1920s and warehouses and factories from the 1940s. The area's first act of transformation began in 1999 when the late world-renowned painter Chen Yifei and several other artists and fashion designers set up studios in the old factory workshops on Taikang Road's Lane 210.

Around 100 shops and cafes moved in after the early buzz proclaimed the area as Shanghai's SoHo. But development stopped a few years later after the district announced plans to tear down the old flats and warehouses to create space for a commercial real estate development.

Opposition was swift and furious. The People's Daily carried essays lamenting the

loss of local culture. Among the other important voices raised against the plan, Zheng Rongfa, then administrative head of the Dapuqiao area where Taikang Road is located, lobbied his government superiors. At the end of 2004, in a rare act of art triumphing over commerce, the preservationists won. The commercial development plans were scrapped and Taikang Road's second act began.

Wu Meisen, planning director of the Taikang Road Creative Industry Center, is leading the charge. He described his organization as a private company with "indirect" support from district government.

After surmounting the 2004 crisis, Wu's next worry was how to satisfy growing demand. There were 114 studios and boutiques in the area, and Lane 210 was almost fully occupied. Wu's company was receiving constant calls from artists asking for space.

Creative Park gradually expanded to neighboring lanes. At the end of 2004, a resident named Zhou Xinliang became the first to rent his 33-sq-m room to a fashion designer specializing in leather. Today Tianzifang is home to around 200 shops, cafes and galleries, run by people from some 20 countries. In 2006, it was named the country's best creative park by the China Guanghua Sciences and Technology Foundation and China Youth Daily, and the best in Shanghai in 2007 by the Shanghai Creative Industry Center.

On weekends as many as 6,000 people walk around Taikang Road's crowded lanes.

"I love this place because it is not a fiction like so many other creative parks in Shanghai," says Liu Xie, an editor who visits there almost every week. "Here, I can feel the real nongtang (lane) life from my childhood."

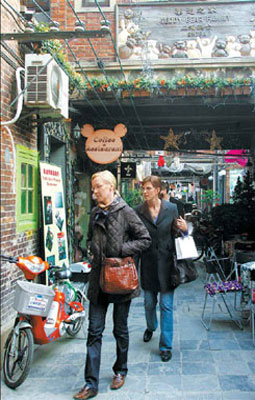

Building interiors have been renovated and given a new coat of paint, but the old brick facades are much as they were decades ago. Middle-aged housewives carrying bags of vegetables squeeze past expats sipping cappuccino at outdoor cafes. Washing hangs from balconies while new-age music spills through boutique windows.

"Though it doesn't look as neat and tidy as Xintiandi or M50, it reflects the true life of old Shanghai," says Li Jialing, a fashion designer who runs the Feel Shanghai studio in the area.

"Disorder-maybe that's not quite the right word-is the biggest charm here."

Elyse Singleton, an Australian expat, enjoys the area's human scale in a city packed with malls and skyscrapers.

"I also love the fact that you can find independent designers and one-off boutiques and cafes that you can't find anywhere else in the city. I also love the atmosphere-cafes with alfresco dining, narrow alleyways, creativity ."

For the artists, craftspeople and shop owners, one of the chief attractions is the availability of small studios at relatively low cost, especially compared with the M50 art complex in the Moganshan area and the Xintiandi entertainment complex, where rents are stratospheric.

A typical studio off Taikang Road is 20 to 30 sq m and rents for around 3 yuan (41 US cents) per sq m a month. Rents are higher at M50 because the studios are much larger, and in Xintiandi, the price is $25 to $35 per sq m per month.

"Not many artists in Shanghai can afford the cost of running a studio over 200 sq m; that's why some artists move here from M50," Wu says. "That's the major reason for the success of Taikang Road-it is small and unique."

As quickly as the area has grown since 2004, even more rapid expansion is on the horizon. The number of studios is expected to triple to more than 700 over the next two years as the project expands west to Ruijin Road. At that time, the floor area of the stores will comprise 75,000 sq m, surpassing the scope of Xintiandi. The Luwan District government will become more involved in the Taikang Road project and set up a formal administration office next year, according to Wu.

"In two years, we can compete with Xintiandi, with our unique feature being the sense of community life."

Though rising property values are causing some residents to move out, Wu intends to maintain his main selling point by zoning off some areas from commercial development. The better-maintained homes, especially those with indoor toilets, will not be rented out. And some rooms on the second and third floors that are difficult to lease will be renovated into family hotels.

"The principle is not to allow development to ruin the original atmosphere," he says.

That may be easier said than done, given the development arc that typically occurs in areas where struggling artists draw a crowd-witness New York's SoHo and countless other places that have been transformed by gentrification.

According to photographer Deke Erh, whose studio has long been in Lane 210, "Art doesn't exist only in the national museum or in galleries. Art is everywhere, and Taikang Road proves it. My worry is that rents might rise so high that artists can't afford to stay here."

Left: Cafe Dan, run by a Japanese couple, charms with its warm atmosphere and quality coffee. Right: Visitors enjoy snacks in the creative park. (photo: Shanghai Star)

(Shanghai Star February 16, 2008)