Global poverty can still be cut in half by 2015 if rich countries lower trade barriers and boost foreign aid, and poor countries invest more in the health and education of their citizens, says a new World Bank report launched at the World Bank/IMF Spring Meetings.

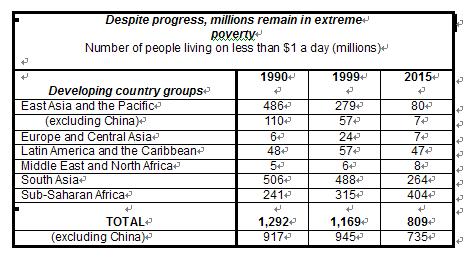

If worldwide economic growth stays on track, global poverty rates will fall to less than half their 1990 level in 2015, pulling some 360 million people out of grinding poverty, says the World Development Indicators (WDI) 2003. But the driving force behind this progress – rapid growth in Asia and improvements in Eastern Europe – will do little to reduce the crushing poverty in Africa, where the number of poor is likely to climb from 315 million in 1999 to 404 million in 2015, and in the Middle East where poverty is also on the rise.

The new report – a large and detailed collection of data from international and national statistics agencies – tracks the progress by poor countries toward reaching the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The goals, agreed by the international community in 2000, aim to reduce income poverty by 2015 and spur big improvements in education, gender equality, health care, and in overcoming hunger and environmental degradation.

“Many developing countries have made great progress in recent years in achieving faster growth and managing their economies better,” says Nicholas Stern, the World Bank’s chief economist and vice-president for development economics. “But growth alone will not be enough to halve poverty by 2015. Developing countries need to ensure that all people, and especially poor people, have access to education, health care, and put in place the right investment climate to create opportunities, spur productivity and make real improvements in people's lives. But they can only do that if rich countries reduce their trade barriers that limit poor countries’ potential to export and grow their economies. We hope that rich countries will follow through on their aid commitments, and will also take action on trade, particularly on agriculture, at the upcoming WTO meeting in Cancun.”

The new Bank report points to alarming disparities between the quality of life in rich and poor countries. While seven of every 1,000 children in rich countries die before the age of five, that number climbs to 121 of every 1,000 children in the poorest countries. While 14 out of 100,000 live births in rich countries result in the death of the mother—that ratio may be as high as 1,000 deaths per 100,000 live births in some poor countries. And while rich countries have achieved the goal of educating all girls at the primary school level, progress lags behind in places like South Asia where only 61 percent of girls complete primary school.

The new report shows that the 1990s witnessed rapid progress in reducing the number of people worldwide who live on less than $1 a day, with numbers dropping from 1.3 billion in 1990 to 1.16 billion in 1999. But these gains occurred largely in China and India. The number of poor rose in Eastern Europe and Central Asia from 6 to 24 million, from 48 to 57 million in Latin America, from 5 to 6 million in the Middle East/North Africa region, and from 241 million to 315 million in Africa.

Looking ahead to 2015, the report says that if economic growth is sustained, the number of people living in extreme poverty is likely to fall in all of the world’s regions except Sub-Saharan Africa, the Middle East, and North Africa, where projected growth will not be enough to stem the rising number in poverty (see chart below).

Barriers to Trade

The new Bank report says that if rich countries lower their trade barriers, it could boost annual growth in developing countries by an extra 0.5 percent over the long run – and lift an additional 300 million people out of poverty by 2015.

“Trade can spur development by expanding markets for developing country exports,” says Stern. “Poor countries are facing huge rich country barriers in exporting those products that play the best to their comparative advantage – namely agricultural goods and textiles.”

Stern cautions that developing countries also have much to gain by lowering their own trade barriers. Countries that have integrated more with the world trade system have on average enjoyed stronger growth. During the past decade, countries that boosted their trade grew more than three times as fast as those that did not.

After expanding by 8 percent a year in 1990-2000, global trade grew by only 1.2 percent in 2001. High-income countries, which account for more than 75 percent of global trade (exports plus imports), experienced the greatest slowdown, with trade growing by only 0.3 percent in 2001. But trade by low-income economies grew by 6.4 percent, almost twice the average rate in 1990-2000.

Although trade in services has grown rapidly, trade in merchandise – primary commodities and manufactured goods – continues to dominate. Exporters of primary non-fuel commodities saw their trade volumes increase, but a continuing decline in their terms of trade left them with less income. Sub-Saharan Africa was hit particularly hard.

While trade can boost prospects for the developing world, foreign aid is also instrumental in giving poor countries the resources they need to invest in their people. In the past year, there have been some promising signs that rich countries are living up to their commitments to increase foreign aid. But Stern urges rich countries to stay the course.

“Agreements and commitments alone will not achieve the Millennium Development Goals,” he says. “More actions are needed. And more resources. The cost of achieving the goals is likely to run to at least an additional $50 billion a year from rich countries over and above the resources from developing countries themselves. Developing countries have been improving their policies and governance, and rich countries their allocation of aid. The result is that aid is becoming still more productive.”

Investing in Health and Education

While trade enables poor countries to export their way out of poverty, it is strong health and education services that give people the tools they need to take advantage of opportunities in the global marketplace.

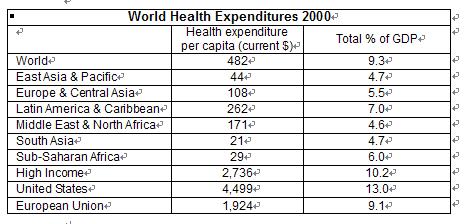

In fact, promoting literacy and enhancing health and nutrition often rank as the most critical measures for the poorest people – and those they value most. But government spending in these areas remain low in many countries. In 2000, public spending on health in low-income countries averaged 1 percent of GDP, compared with 6 percent in high-income countries.

“As rich countries grow older and their working population shrinks, poor countries have an opportunity to create jobs and increase the productivity of their growing work force if they invest more in the health, education, and nutrition of their people,” says Eric Swanson, Program Manager of the Development Data Group. “But the poorest countries will need help to increase the capacity and effectiveness of their health and education systems.”

Spending on Health

The study finds that in 2000, total (public and private) health spending in rich countries was 10 percent of gross domestic product, while low income economies could manage barely 4 percent. And this does not go very far: rich countries spent $2,700 per person on health care per capita while African countries spent only $29 per capita, and some as little as $6 per person. Total health care spending in the US was $1.3 trillion or 13 percent of GDP and represented 43 percent of total global expenditures on health. Low-income economies spent only $45 billion.

Meanwhile, private expenditures on health represent a larger share of health spending in poor economies than in most rich economies. In poor countries, 73 percent of spending was from private resources; in rich countries only 38 percent was private. The United States is unusual among rich countries – 56 percent of health spending was private; in the European Union 25 percent was private.

Spending on Education

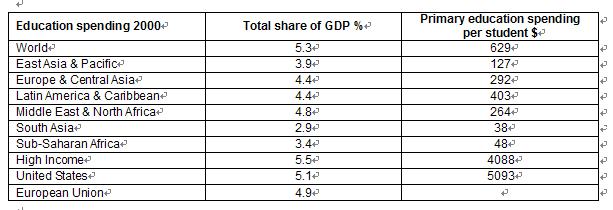

While health spending falls woefully short in poor countries, spending on education also pales in comparison to rich countries. Although global public spending on education amounted to $1.54 trillion per year, 85 percent of that was in rich countries.

Average per capita spending on education was 28 times greater in rich economies than in developing economies. Public spending as a share of GDP was somewhat higher in high income economies (5.3 percent of GDP) than in developing countries (4.1 percent of GDP), but the big difference in total spending is owing to the resources – GDP – available to them. Low-income economies spend proportionately more of their public education budgets on primary education.

These shortfalls in both health and education spending come at the same time as the world military spending in 2001 is estimated to be bout 2.3 percent of global income or more than $800 billion a year. In more human terms, military spending is about $137 per person in the world. This estimate is based on adopted defense budgets and is likely to be revised upwards when supplementary expenditures resulting from the 11 September attacks on the USA and the ensuing war on terrorism have been taken fully into account.

Investment Climate

The Bank study also points to the need for countries to create sound investment climates that can encourage job creation and spur economic growth.

Good macroeconomic management, trade and investment policies that promote openness, and good-quality infrastructure and services are all essential. They also need a conducive business environment—based on a legal and regulatory system that supports the day-to-day operations of firms by protecting property rights, promoting access to credit, and ensuring efficient tax, customs, and judicial services.

Part of what determines the business environment in a country is the regulation of new entry and countries differ significantly in the obstacles they impose on the entry of new businesses. In Mozambique, for example, entrepreneurs wishing to start up a business must complete 16 procedures, a process that takes an average of 214 business days and costs the equivalent of 74 percent of gross national income (GNI) per capita. In Italy, they must complete 13 procedures, wait 62 business days on average, and pay 23 percent of GNI per capita. But Canada requires only 2 procedures, and the process takes only two days and costs about 1 percent of GNI per capita.

“The case for creating a good investment climate is simple: an economy needs a predictable environment in which people, ideas, and money can work together productively and efficiently,” says Stern. “Small firms and farms suffer most from a weak investment climate. Countries should focus on improving the investment climate for domestic entrepreneurs because 90 percent of investment comes from domestic sources. But a better investment climate will also attract foreign investors. And countries that receive more foreign investment—an important conduit for new technologies, management experience, and access to markets—enjoy faster growth and greater poverty reduction.”

(China.org.cn April 14, 2003)