Rarely in Chinese films about that massacre, in which about 300,000 civilians and soldiers lost their lives, are Japanese soldiers portrayed as human beings and not as monsters.

In Lu's film, soldiers share happy moments making a pot of tasty soup, and one young trooper falls in love with a comfort woman. It was the first time he ever had sex.

At the same time, these soldiers were part of an army, which operated under a strict code of discipline and became a fine-tuned killing machine. But Lu does not demonize them.

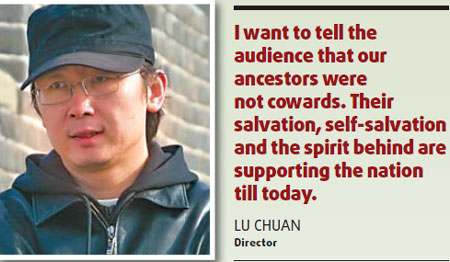

"Demonizing your enemy is insulting yourself," Lu says. "We must face the question that who defeated us 72 years ago. Otherwise we never really learn from the massacre."

Lu cast about 50 Japanese actors in the $12 million film. He chose actors who had never set foot on mainland soil and probably experienced the same culture shock as their characters did when they arrived in China.

To prepare the Japanese actors, who knew nothing or little about the history, Lu took many historic photographs and old film footage to Japan.

He promised Japanese actors he would not demonize them or portray them as clowns in the film. The director also told the actors to perform in the same way they thought their great grandfathers would.

"Maybe I cannot make myself love the Japanese troops, but I try to understand them," he says.

As the actors began to live and breathe their roles, the off-screen relationships between the Chinese and Japanese actors changed.

The two groups hardly talked with each other during the eight months of shooting.

There was even a fight after one Japanese actor accused a Chinese film extra of not devoting himself to the work.

"I can feel how estranged the two peoples are," Lu says.

The director believes there are three ways to solve China-Japanese relationship problems.

"First, we destroy Japan. Second, Japan destroys us," he says. "Or the third way is we try really hard to understand each other.

"I think we should choose the third way.

"The Japanese should apologize for the massacre, and Chinese should reflect on why we lost and whom we lost to."

Renowned humanitarians, such as John Rabe and Minnie Vautrin, who set up a safety zone in Nanjing and sheltered about 200,000 Chinese, were given an "appropriate proportion" in the film, Lu says.

Their frantic protection of Chinese people and great pain of witnessing the atrocities are fully displayed, but in Lu's film, the two sides in war were the focus.

"I respect Rabe and other Westerners who helped us a lot, but this war in my understanding is not about how a Westerner saves hundreds of thousands Chinese," he says.

"It is at first about Chinese and Japanese. The primary thing for both of us is to face the history and learn from it."

(China Daily, April 14, 2009)