|

|

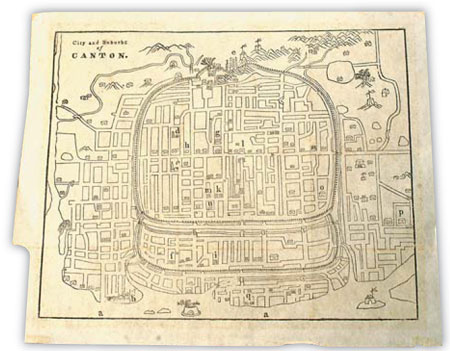

City map of Guangzhou, one of the maps that the Nobel-winning economist Robert Mundell studied during his visit to Tam's studio last November. [Edmond Tang]

|

But how to ascertain an old map's authenticity?

"A gut feeling is important," says Tam. "You know subconsciously if a map looks and feels genuinely old." Inimitable, fine engraving is often a big clue. Browning, holes, tears, water marks or even candle wax - all damage as they are - are also sought-after, tell-tale signs.

Tam nevertheless takes no risks with his purchases and has been served well by personal experience.

"European paper made between 1700 and 1800 usually has watermarks, which were the paper maker's emblem and could be seen through transmitted light," he says.

"All you need is a good eye and copious dedication."

Put another way, the bottom line is that Tam accepts the potential for doubt. "With an old map, no one can have the last word," he says, referring to the perennial debate over some of the world's hottest maps. "A map conceals as much as it reveals."

In November last year, Tam received a call "out of the blue" saying that Robert Mundell, the flamboyant Nobel Prize-winning economist and close friend of Premier Wen Jiabao, was interested in his maps. A few days later, Tam was busy de-cluttering his Causeway Bay office to prepare for the arrival of the "Father of the euro".

"Mundell asked to see 19-century city maps of Guangzhou and Quanzhou, two places that were the earliest settlements for foreigners," says Tam. "He was particularly interested in those showing city walls." The two men talked for about three hours - two on maps, one on the international monetary system.

"He said nothing about his intention but my guess is that he was trying to garner ideas for a new monetary system that he might be designing," says Tam. "What a walled city and a monetary system have in common is the inclusion and exclusion of resources."

The visit confirmed Tam's belief that old maps hold modern messages, the most important one being the mapping process itself.

"Maps belie the entire trajectory of human understanding, by preserving all their detours and misconceptions," he says, pointing to a 1685 Dutch map, in which China resembles a giant piece of toast.

Tam believes maps have an ever-more important role to play.

In April 2005, four months after the devastating Asian Tsunami, he exhibited his satellite maps of the Indian Ocean at major railway stations in Hong Kong. In retrospect, the countless white vortexes that filled the surface of the ocean hours before the disaster struck seemed to be clear warning signs.

"The human tragedy would have been reduced if we had known how to read these maps," he claims.

The call of maps has taken Tam around the globe but the day will come when he'll stop to rest.

"The saddest thing that could ever happen to a collector is to have his collection dissolved posthumously," says the 58-year-old. "I will not let that happen."

Over the years, Tam has donated over 10,000 old maps to libraries, universities and other cultural institutions in Hong Kong.

He is now in talks with the government of the United Arab Emirates to build the world's largest map museum and is also keen to find partners on the Chinese mainland.

"Life is short and maps remind us that we are not mere passers-by, but observers and recorders of our times. They guide us to our own treasure island."

(China Daily January 14, 2009)