It looks like any ordinary quadrangle in Beijing.

But behind a fading red wooden door, hidden in a hutong near Jingshan Park, is a small museum of Chinese avant-garde art: Yue Minjun's symbolic bald-headed smiling statue squatting on a table, Li Yong's wooden horse standing by the sofas, and on the floor, a dozen hen statued at every corner of the house, the work of Duan Jianyu. Several art books and magazines are piled in the corner and a big LCD TV, the only luxury item in view, plays short avant-garde films.

|

|

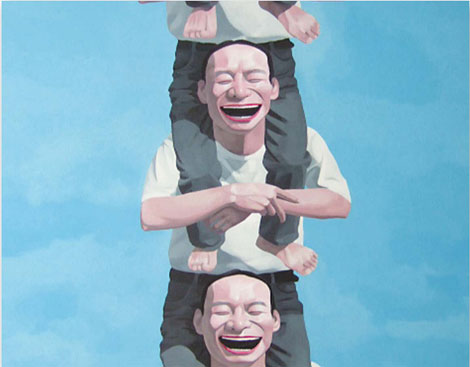

Everybody Connects, an oil on canvas by Yue Minjun. Works by Yue and other modern Chinese artists are currently fetching very high prices at international art auctions in Asia.

|

It is the studio of Karen Smith, one of China's most active foreign art critics and curators. The UK-born scholar has lived in Beijing for nearly 20 years and witnessed the boom of Chinese contemporary art. Her book, Nine Lives: The Birth of Avant-Garde in New China, claims to be the first systematic study of Chinese avant-garde art by foreign critics.

Talking with Karen in her small courtyard, where bamboo and chrysanthemums grow, is a delight. Anything but the usual stern-looking critic, this middle-aged woman is mild and elegant, with an impressing soft voice and warm smile. Only her penetrating eyes and the continuous interruption of visiting artists during our talk give away her identity.

"Many people have asked me why I've stayed here for so long," she says. "The answer is simple - here I can explore Chinese avant-garde art as completely as possible - and this is my lifelong aim."

Back in 1990, Smith was working in Hong Kong as editor-in-chief of the art magazine Artention. Well placed to identify trends in the art world, she was drawn to examples of China's avant-garde art she came across in the territory. Astonished to discover that nothing had yet been written about this new art, by the end of 1992, and with Artention under threat of closure from its new owners, she moved to Beijing to study Chinese so she could research material for a book, filling what was clearly an enormous gap in the field of art history.

Today, hundreds of books have been published on China's new art but Smith's work has the stamp of first-hand knowledge, offering a complete record and systematic analysis, combined with a human touch. Having lived in China for 18 years, Smith has witnessed everything she has written about and made good friends with numerous Chinese artists like Fang Lijun and Di Jianli.

But Smith is not just an onlooker. She has established a niche as an important focal point and resource for all involved with the China art scene. In June, she organized the first screening of 33 short films showcasing 25 Chinese artists at London's Southbank, Britain's largest arts center. She also arranged an exhibition of contemporary Chinese art at the prestigious Tate gallery, hailed as the most comprehensive -and controversial - collection of Chinese modern art ever staged in the UK. Now she is busy preparing a grand photo exhibition portraying China during the past 60 years, and several unique photos will be shown in public for the first time.

"I am trying to get people interested in the dynamics of a cultural framework, with a long dynastic and political history," Smith says.

But more touching is her deep feeling for art, and Chinese artists in particular. Some critics accuse them of being motivated by quick fame and money but Smith is more generous. "If you put yourself on the line to create a work of art, no one ever does that lightly," she says. "And every time someone creates a work of art, they are actually putting something of themselves out there."

But she also tempered her enthusiasm with caution. "Even though I have a critical eye, there are people who you really want to succeed," she admits. "So sometimes you look harder. It generates a different impression of the artwork's value." Smith even put some distance between her and those featuring in her book. "I started to withdraw because I felt I had to take a step back," she says. "Consequently, our conversations became more serious and thoughtful."

After living in Beijing for so long, Smith hardly even sees herself as an outsider any more. She speaks fluent Mandarin and often lines up to buy old style Beijing cakes while chatting with her neighbors. To welcome visitors at her home, she has even made a massive table big enough to take 20 people at one sitting. She is familiar with the same problem that has long afflicted Beijingers in old quadrangles - leaking rain. She never thought of moving to modern apartment buildings, though, preferring to do the repairs herself. "It is the unique flavor of living in Beijing and necessary experience for anyone who want to infuse in the culture, isn't it?" she says.

Asked about the future, she says: "I will never leave China. It is where I have found the roots of my career and the real meaning of my life."