Li Tiansheng has business cards that list five titles. The first four are affiliations with music associations from across China.

The final entry is: "famous king of folk songs".

The 80-year-old singer has certainly earned this nickname. Throughout his long career, music has taken him from dreary rice paddies to the Great Hall of the People and, most recently, to an international celebration of Hakka culture in Fujian province.

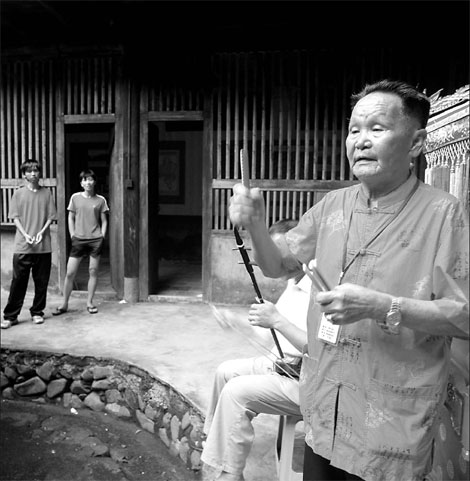

Li Tiansheng sings in a tulou in Yongding, Fujian province during the Fujian (Yongding) Tulou Hakka Cultural Festival.

Earlier this month, he was one of the featured Hakka celebrities invited to perform at the Fujian (Yongding) Tulou Hakka Cultural Festival and Sixth Longyan Tourism Festival. The song and dance gala celebrated the recent announcement that tulou, traditional Hakka fortified dwellings, have been listed as UNESCO World Cultural Heritage sites.

"That night I thought, the best topic is a journey to the southern seas," he said.

At the festival, he sought out someone to play the erhu, a traditional two-stringed bowed instrument, as accompaniment. Li moved with surprising agility over slick stone steps, dodging puddles and a gaggle of bedraggled ducks.

Deeply tan and considerably tall, Li remains unbent from years of working in the fields. Although he earned his fame with his songs, he claims music is not his profession. He is still a farmer.

"It's why I'm so healthy," he said. "I still raise fish and help bring in the harvest."

The tulou's pale earthen walls dwarfed him. In true Hakka fashion, every doorway he stepped through was framed with strips of red paper covered with auspicious greetings.

Draped in a festive red shirt, Li began to sing. The lyrics were simple, roughly translated as: "Brother is sailing for the southern seas. Wishing him good health on his journey, I light incense in his honor."

His nasal, melancholy singing style is characteristic of northern China, the root of Hakka ancestry.

"It's what the people love to hear," he said. "It's like a conversation."

Born in 1928, Li was his parents' only surviving child. His father died later the same year. Without even elementary school education, Li spent his childhood toiling in the fields. When he was 13, the village elders noticed the boy had a good voice. They began to teach him traditional folk songs.

"My cattle were my first audience," he said. "I felt like a shepherd."

Throughout his teens, his singing steadily grew in popularity. When he was 18, he added percussion accompaniment. He made a set of zhuban, a stack of polished bamboo strips akin to the kuaiban of Tianjin. Li got the idea from Cantonese beggars in his town, who used them to attract people's attention.

At age 22, less than ten years after he began to sing, Li appeared at the Great Hall of the People. More than 1,000 contestants nationwide had vied for the honor.

This time his audience was Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai, Zhu De and Liu Shaoqi. Li was the last to perform. While he waited his turn, the young man felt thoroughly rattled.

"People said: 'You are in your 20s. Why would Chairman Mao want to meet you?'" he recalled. "I was very nervous."

For years, he treasured a large framed photo of him posing with Chairman Mao. But the "cultural revolution" (1966-76) soon caught Li in its clutches, when the picture of him and Mao and stacks of vinyl records of his singing were destroyed.

He didn't sing again for 20 years.

In 1979 Deng Xiaoping took the first steps to limit population growth by implementing a one-child policy. But how to take the message to remote villages? Government officials remembered Li. They thought he could reach the people with his voice.

The "cultural revolution" was over, but memories of persecution made it a tortuous decision to participate in the campaign. Li's wife, sons, and singing teacher were against it. It took six people, including members of the media and local officials, to convince Li to sing again.

"They told me, it's OK now," he said. "They promised. So I gave in. I sat down to write a new song on the theme that night, and finished it by midnight."

Li wrote ten verses praising the new government policy, performing them for television reporters from Beijing, Shanghai and Fujian.

"More children do not mean more prosperity. Many women have learned this lesson," were his lyrics.

If the lyrics sound a little bitter, it's because Li learned from personal experience. He has four sons and three daughters whom he struggled to feed and clothe.

The message had the desired effect. In a 2000 report, a couple surnamed Lin was allegedly so moved by Li's song that the two signed a contract at the town's birth control agency promising not to have a second child.

Li's singing career has given him the opportunity to travel abroad. In the 1990s, he left China for the first time. He has since visited Japan, Singapore, and Italy.

In 2002, he was one of two Hakka musicians to perform with the Xiamen Philharmonic Orchestra in the state of Connecticut. A translator helped the Western audience understand his lyrics.

Li, then 74, claimed to like everything about America except one thing: raw salads.

"Italy had better food," he said. "I wasn't used to being without rice."

(China Daily July 24, 2008)