A court in Inner Mongolia has been urged repeatedly to reopen the case of the brutal rape and murder of a woman in 1996, in which an innocent man was executed and another man who confessed to the murder sits in jail with no future trial in sight.

Hugejiletu was put to death in June 1996 on charges of rape and murder of a woman in the bathroom of a textile factory in Hohhot, capital of the northern region of Inner Mongolia, according to the Guangzhou-based Nanfengchuang Magazine this week.

Hugejiletu's elderly parents have been petitioning the High People's Court of Inner Mongolia every Wednesday to begin prosecution of the man who confessed to the crime in 2005 and amend the family's loss.

"They told me that they sympathized with my son and that my son's death was unjust. But they never gave us any hope," Hugejiletu's parents were quoted as saying after a second visit to the regional high court in June.

Hugejiletu had reported the case to the police after the incident and according to an alibi obtained by the magazine, had maintained his innocence one month before his execution.

The confessor, a man named Zhao Zhihong, said in October 2005 that he killed 10 people in Inner Mongolia, including the woman raped in the factory, according to the magazine.

A year later, the local judicial department set up a special investigative group to review the case, but little progress has been made.

Zhao remains in detention and has not been brought to trial.

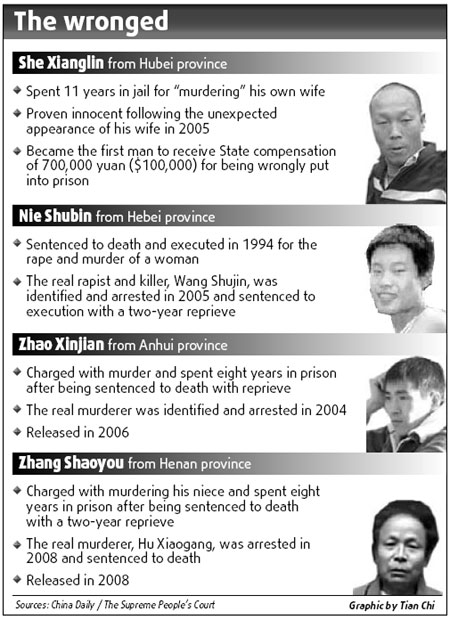

Hugejiletu's case has been the latest discovery of wronged criminal cases in China, which many law practitioners said were caused by forced inquisition by local prosecutors.

Song Jihu, a Beijing-based lawyer with the Zhongji Law Firm, told China Daily that the prosecutors likely sacrificed fairness for efficiency in Hugejiletu's case. He said prosecutors normally want to deal with as many cases as possible.

"The problem is some prosecutors at lower levels just want to finish the cases quickly," Song said.

"They often coerce suspects to admit their crimes and capital punishment is often given randomly, especially before the Supreme People's Court began reviewing all death sentences starting in 2007."

Despite the fact that forced inquisitions are still inevitable under the current legal system in China, it is also a common practice for the courts to review the case as soon as they find new evidence that proves the original suspect was wrong, said Chu Fumin, a prosecution scholar with Peking University.

China has slowly been reforming its death penalty system after acknowledging that several injustices have been made.

The Supreme People's Court (SPC), which has the sole power to review and ratify all death sentences, said last week that it will decrease the number of death sentences and tighten restrictions on the use of capital punishment.

As a result, an average of 15 percent of sentences were overturned in 2007 and 10 percent were overturned in 2008, insiders told China Daily earlier.

Death sentences are given only to those who have committed extremely serious or heinous crimes that lead to grave social consequences and the highest court exercises extreme caution in handing down the death sentence to those guilty of killing family members or neighbors over disputes, said Zhang Jun, vice-president of the SPC.

Calls to the criminal tribunal and case registration department at the High People's Court of Inner Mongolia went unanswered all day yesterday. A staff member at the administrative office of the court told China Daily the case was "very sensitive" and declined to provide information on whether a retrial will be held.

(China Daily August 7, 2009)