|

|

|

The new biography tells of the first 45 years of Deng Xiaoping's life, as a revolutionary, soldier, commander and reformist. |

Over the past 60 years, the world has witnessed China's rise from being an under-developed "sleeping dragon" to the world's third largest economy.

Some historians and politicians, however, still cannot come to terms with how this happened. They wonder why China did not follow the model that the developed West paved via its capitalist and industrial revolution.

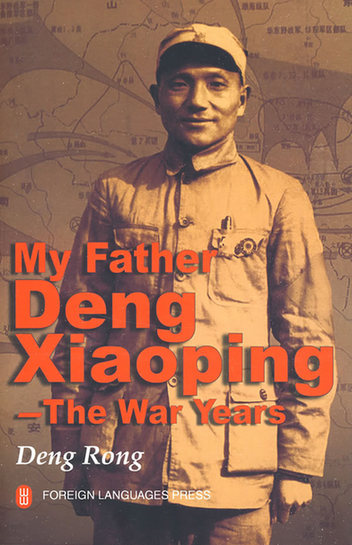

Some answers may be found in biographies of the founders of the People's Republic of China, such as My Father Deng Xiaoping - The War Years, written by Deng Rong, the youngest of Deng's three daughters. Its English-language version, translated by Lu Min and a few other veterans, has recently rolled off the presses of China's leading English language books' publisher, the Foreign Language Press, to mark the 105th anniversary of Deng's birth.

Although quite a few people have written about the life of the former leader, Deng Rong's account is unique. As she says in the preface: "I was born and grew up in a special environment. I had first-hand experience of history in the making.

"Many historic people surrounded my life, and many historic events unfolded around my family and me. The events and experiences and environment that I have recorded here should not be lost or forgotten," Deng Rong writes.

Additionally, Deng Rong worked as a personal assistant to her father after the chief architect of China's reforms retired in 1989. Between 1989 and 1993, the year when Deng passed away, Deng Rong had plenty of time to study her father's life.

As she traces her father's childhood years and sifts through his long career as a revolutionary, soldier, commander and reformist, her narrative offers persuasive reasons as to why China has not followed Western democratic systems but instead created its own model. Although there have been ups and downs in the past six decades, China has steadfastly held onto its own systems, with Chinese characteristics.

Deng was born in 1904, in Guang'an county, a poverty-stricken and mountainous part of Sichuan province, where residents had to walk to the nearest big cities hundreds of kilometers away. Here learning was the only way to escape. As the eldest boy, Deng started to read and write at 5 and went to school at 6.

In those years, numerous Chinese - from the landed gentry to scholars and youths - looked to the prosperous West for ways to lead China out of feudalism and imperialist colonization. The fashion, then, was to study overseas for new ideas. As such Deng's father sent his son to a prep school in Chongqing, in 1919, to prepare for further studies in France, which was then a symbol of liberty and freedom.

The school had neither dorm rooms nor sports facilities. The lessons were in French and technical training was systematic.

Besides attending classes, the aspiring youths also paid attention to events outside the school that impacted the country. When they heard the Chongqing police chief had swindled public money to buy and sell Japanese goods for personal gain, they joined in a student demonstration outside the police headquarters, demanding the police chief hand over the Japanese goods. The two-day demonstration ended with the police chief's resignation and the ill-gotten gains being burned.

On Aug 28, 1920, six days after Deng celebrated his 16th birthday, he boarded a ship with some 80 other Sichuan youths for France. It took some seven weeks before they arrived in Marseilles.

The glistening high rises, trolley cars and automobiles were a sharp contrast to the small rural county where Deng was from. But Deng's life was frugal and after five months of classes at a private middle school his money ran out and he had to find a job to earn money before he could continue his studies.

He first worked as an apprentice steel worker at the Le Creusot Iron and Steel Plant in La Garenne-Colombes, a southwestern suburb of Paris. Though the job was tough, Deng earned between 12 to 14 francs a day. He lived in a crowded dorm with 20 other Chinese youths, some 20 km away from the plant. At the end of the first month, he discovered that he owed some 100 francs, though he only lived on tap water and bread.

During his five years in France, Deng took up various jobs, including a job as a fitter at an auto plant, but he was unable to earn enough and continue his education. France was suffering from economic recession and he experienced great hardship, saw the suffering of French workers under capitalism and learned about the workers' movement.

He also learned how the French authorities collaborated with northern warlords in China to smother the young republic founded by Dr Sun Yat-sen. Staffers at the Chinese embassy did very little to support the poverty-stricken overseas Chinese students. They even cooperated with the French authorities in cracking down on student leaders, who were fighting for their welfare.

On May 30, 1925, British police in Shanghai killed five students who were demonstrating against the death of a child laborer in a Japanese textile plant. The murder aroused anger among the Chinese, who staged citywide strikes. However, the major imperialist countries - including France, the United Kingdom, the United States and Japan - sent warships to Shanghai to suppress the uprising.

While in France, Deng met with members of the Communist Party of China and studied their books and magazines. He was drawn to the ideas of revolution, and was critical of the French system. Later, he became a Communist Party member, working with Zhou Enlai, who would become New China's first premier. In January, 1926, Deng returned home to join the revolution.

To detail her father's life after he returned from France, Deng Rong had to wade through the annals and research the places where her father worked underground in Shanghai, organized uprisings, edited newspapers, or directed battles before and during the Long March.

The chapters chronicling the major campaigns Deng and other prominent Communist Party of China army generals waged against the Japanese imperialist army during World War II and against the Kuomintang army give insight into Deng's wisdom and personality.

Meanwhile, she also shares anecdotes and tells of intimate moments in the life of Deng so that he is revealed not only as an official, but also a caring husband and a loving father.

Deng's first wife was a revolutionary, but she died in childbirth in 1930. His second wife left him when Deng was stripped of his job in 1932, after he expressed opposition to the leftists' rules that put the Party and its army in jeopardy.

It wasn't until 1939 that Deng met Zhuo Lin and took a liking to the university student-turned revolutionary who was being trained in Yan'an, Shaanxi province. Deng wasn't daunted even after Zhuo said she was too young to get married. After further meetings and finding they had a lot in common, Zhuo accepted Deng's marriage proposal. Their marriage endured despite the trials that would come.

True to the title of the book's last chapter, An Unfinished Story, the book only tells of the first 45 years of Deng's life, but his name was already written in the hall of fame at the time of the birth of New China.

(China Daily August 25, 2009)