|

|

|

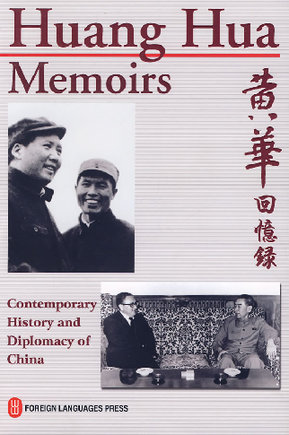

Huang Hua's Memoirs:

Contemporary History and Diplomacy of China

Foreign Languages Press, Beijing, China, 2008

Available in major bookstores

|

Reviewed by Lin Wusun

Writer's note: Huang Hua, 96 in age, is the only Chinese statesman alive who has participated in and witnessed the development of modern Chinese diplomacy from its very inception. He is also lone survivor of the "Three Red Bandits", i.e. the American journalist Edgar Snow, the American doctor George Hatem and Huang Hua, who braved serious threat to their security and life to join the Chinese Red Army soon after its arrival in Northwest China after the Long March.The present review of his recently published memoir is a fuller version of the one which appeared earlier in China Daily.

After retirement from their official posts, Chinese diplomats used to keep a low profile. Some continued to serve in non-governmental organizations. Most just faded away. However, this is no longer the case. Quite a number now serve at NGOs, teach at universities and /or appear on TV interviews. Still others write memoirs. Some years ago, World Knowledge Press started a series in which retired diplomats recalled important and interesting episodes they personally experienced. Qian Qichen, former State Counselor and Foreign Minister, created publishing history when he authored a popular book called "Case Histories in Diplomacy", expounding the principles and practice of Chinese diplomacy.

And now we have the benefit of reading the Chinese and English language memoirs of Huang Hua, veteran revolutionary, senior statesman and diplomat – ambassador, foreign minister, vice premier, and vice chairman of the Standing Committee of the National People's Congress. It is unique in that it provides us with tales about the source and 70–year development of modern Chinese diplomacy, based on the author's own experience and materials from the Chinese Foreign Ministry archives. As the author is now 96, his memoir covers an unusually protracted period, from the 1930s to a few years ago. Besides, having served as ambassadors in different parts of the world, often taking part in significant international conferences and other types of negotiations, and finally as China's foreign minister, Huang Hua dealt with China's relations with all types of countries, especially the major ones. While it was written in a matter-of-fact way, it does not lack profound observations on the making of history.

But let's start from the book's beginning in the 1930s, when Huang Hua was studying at school and university. This was the period when an impoverished China faced the danger of being subjugated by Japanese imperialist invaders. The harsh circumstances compelled Huang Hua and his fellow young intellectuals to seek ways to save the country and to join the progressive student movement then arising in North China. The severity of the national crisis gave rise to the popular saying, "Though North China is extensive in area, it has no place for a desk where we can study." At the missionary-run Yenching University, Huang Hua was a diligent student supported by scholarship, yet he soon got involved in the salvation movement and became a student leader organizing protest demonstrations against the authorities' non-resistance policy. The dedication and courage of the participants in the face of harsh police suppression was vividly described so that almost 80 years later we can still capture the students' idealistic fervor. Huang Hua's experience in prison, where the faithful continued their study and exchange of views through a secret hand-written publication he edited, showed him and his comrades to be persistent fighters prepared for ever-harsher challenges in the future. There have been many write-ups of this 1935 December 9th Movement, but Huang Hua's account lends a direct source rich and reliable in details. In modern China, there was more than one intellectual movement which had significant impact on the course of the nation's history, the 1935 one and the earlier May 4th Movement of 1919 being the most significant.

Huang Hua had joined the underground Communist Party while at Yenching U. Following his 1935 experience, he decided to forego Yenching's graduation ceremony and join the American journalist Edgar Snow as his interpreter during the latter's coverage of the Chinese Communists in North Shaanxi. The adventure of crossing the Nationalist blockade (Huang Hua is the last survivor of what Snow dubbed at the time as the "three Red bandits, the third one being the American doctor George Hatem), of meeting with Mao Zedong, Zhou Enlai and the Red Army commanders and soldiers, and of hearing their stories of the Long March, as well as the off and on battles they encountered, all brought Huang Hua closer to China's rural realities. The role-model behavior of these men and women strengthened his revolutionary faith and discipline. From that time on till the end of the Resistance War against Japanese Aggression in 1945, Huang Hua stayed mostly in Yenan, headquarters of the Chinese Communist Party. Thus he has been able to give a lively first-hand account of life in the resistance base.

Huang's description of the US Army Observer Group in Yenan, sent there in 1944 to co-ordinate the common struggle against Japanese aggression, is both detailed and fascinating. According to Huang Hua, himself a member of the Chinese liaison group, relations between the two sides were quite cordial, and the "Dixie Mission" members saw how effectively the Chinese Communist-led troops were fighting the Japanese. This relationship could be considered the prelude to New China's diplomacy. In fact, in a directive on liaison work with the Mission, drafted by Zhou Enlai at Mao's request, these prophetic words were written: "Our foreign policy is guided by the idea of forming an international united front...We must be firm in our national stand, but oppose such erroneous concepts as excluding or fearing anything foreign, or fawning on everything foreign. While strengthening our national self-respect and self-confidence, we must also learn from the strong points of others and be adept at co-operating with others."(see p. 76) In a semi-colonial country, where both tendencies were quite common, this reminder was very appropriate and timely. It was to guide all China's foreign dealings following the founding of the young People's Republic in 1949.

Despite this rather auspicious beginning, Sino-US relations were tense and even antagonistic for many decades. Yet it was not caused by the Chinese side. Following Japan's defeat in 1945, the US Administration backed Chiang Kai-shek forces in launching a civil war against the Chinese Communists, disregarding the Chinese people's common aspiration for peace and reconstruction after eight years of destructive war. The tripartite Military Mediation Mission, of which the US was a participant, failed because the Chiang Kai-shek forces never intended to observe any agreement reached and the US side was partial to them. The breakup threw the country straight into full-scale civil war. When the Chiang forces collapsed, Huang Hua was appointed the head of the foreign affairs office of the newly-liberated Nanjing, formerly the Nationalist capital. US Ambassador Leighton Stuart, a long-time missionary in China and a former president of Yenjing University where Huang studied, remained in China. The two met informally on several occasions, and the topic of Stuart's possible visit to Beijing to meet with the top Chinese leaders was broached. However, this northward trip was rejected by the US State Department, which reaffirmed Washington's continued recognition of the Chiang government in Taiwan. Thus, another historic chance for normalizing relations was missed. As the author observes, "It took the US 22 years to re-evaluate this policy."