By Bu Ping

Scholars from China and Japan recently met for the second time in Tokyo under a joint history study program between the two countries. At the meeting, they discussed the research to be carried out, reaching a consensus on specific historical topics that they will study in the coming months. The Chinese and Japanese committees will conduct research on these topics and file reports independently. After that, they will compare notes and issue a joint report detailing their agreements and disagreements.

The scholars also set a timetable for the program. It was decided that they would meet for the third time in December to review each other's reports. The joint report is set to come out in June next year.

The meeting was held in a positive and constructive atmosphere. Scholars from the two countries gained a basic understanding of each other's views while stating their respective positions on some historical issues. Although they did not have time for an in-depth discussion, they took a substantial step and made a good start.

Reshaping regional relations

China-Japan relations have finally been stabilized after many dramatic twists and turns. Many insightful people have underlined the fragility of this relationship. The two countries' political leaders, commentators and media organizations are expected to take this into account and be careful about their words and deeds. As their different evaluations of history have triggered widespread concern, it is imperative that they face up to the problem and come up with a proper solution. That is largely why China and Japan initiated the joint history study program.

Some people have doubts about this program, regarding it as an impossible mission. I would like to make two issues clear to them: first, the standard by which we should judge the process and results of the joint history study, and second, how to define our dialogue partners.

The joint history study program has three dimensions. The first is to create a calm environment where each party can sort out its own views and listen to the opinions of the other party. The second is to probe into each other's views in discussions, during which they may exert an influence on each other. The third is to consider what the real differences are, what issues seem to be differences but actually are misunderstandings and in what areas consensus may be reached. At present, the first dimension has been realized, while the second and third dimensions will soon be put into practice.

Most Japanese people love peace and are critical of the aggressive war Japan waged against its neighbors. This is evident from the fact that the history textbook published by Fusosha Publishing Inc., which shows approval of Japan's aggression, is rarely adopted. These people are our major dialogue partners. However, as the war caused severe suffering to the Japanese people, most of them oppose the war in the belief that the Japanese were victims. We find that this position still falls short of the expectations of the victimized Asian nations.

It is a stark fact that Japan was an aggressor in the war. However, most Japanese are barely aware of this fact. Instead, they tend to associate the war with the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the air raids on Tokyo. These are also facts, but the point is how to analyze them. If they are told about the disasters Japan inflicted upon other Asian nations, the Japanese will easily understand why they suffered from the war.

Unfortunately, Japan's aggression against other countries is downplayed in Japan's history education. That's how the differences in evaluating history arose. It should be admitted that this is different from Fusosha's publishing of the history textbook that purposely whitewashes Japan's wartime history. We need to condemn that right-wing textbook from theoretical and cognitive perspectives. However, it calls for enhanced communication and mutual understanding to bridge the gap between the general public in Japan and other Asian nations in evaluating history.

Differences in interpreting history have persisted over the six decades since the end of World War II partly because of the rampant conservative forces in Japan. More importantly, we should be cautious about the fact that fewer and fewer Japanese today have a direct experience of the wartime history. Statistics show that over 70 percent of the Japanese people were born after the war. People aged from 40 to 60 may get a glimpse of the war through family elders. However, this is not possible for young people in their twenties. For most Japanese, the war is becoming increasingly abstract. This trend may eventually give rise to "narrow nationalism," which is extremely dangerous given Japan's aggressive past. A commonly acceptable evaluation of history not only has political implications but also bears on world peace and development.

Despite the many uncertainties that affect China-Japan relations in the 21st century, there have been strong appeals for reshaping the relationship between the two countries. A survey conducted by Japan's Ministry of Foreign Affairs in February last year showed that 77.9 percent of the respondents thought that China-Japan relations should be improved, while 46.5 percent predicted that the two countries would have more frictions but better relations 20 years later. After Japanese Prime Minister Shinzo Abe visited China in October last year, more than 70 percent of the Chinese people surveyed recognized the need to improve China-Japan relations. Against this backdrop, scholars of the two countries are duty-bound to promote the healthy development of bilateral relations by carrying out the joint history study.

Role of historians

After the end of World War II, the Cold-War mentality valuing realistic goals dominated international relations, hindering the progress of peace and development. In this context, differences in evaluating history inevitably became a stumbling block that made it difficult for nations to develop good relations. Some constructive efforts have been made to resolve these differences. For example, Germany sought to reach a common understanding of history with Poland and France, efforts that contributed to the unity of Europe. As the strained regional relations in East Asia today are largely attributed to the countries' different evaluations of history, it is essential that they take similar steps.

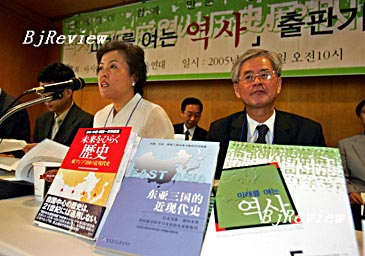

I began to take part in the editing of a joint history textbook, which involved scholars and teachers from China, Japan and South Korea, in 2002. The book was a hit immediately after it rolled off the printing press. It was reprinted several times in Japan and South Korea as the number of orders kept going up. In China, it became a bestseller shortly after it entered the book market. The popularity of the book shows that historical studies can help resolve pressing social issues when their achievements are made acceptable to the general public.

There have long been heated debates on whether China, Japan and South Korea can reach a common understanding of history. What I mean by "common understanding of history" is that they should reach an agreement on the nature of the war and the evaluation of major wartime events.

In a century that is characterized by the pursuit of peace and development, we stand for resolving international disputes through dialogue. This principle also applies when it comes to dealing with disputes over historical issues.

We strongly reject Fusosha's history textbook because it advocates "narrow nationalism." In recent years, this sentiment has been emerging not only in Japan but also in some other East Asian countries. Growing "narrow nationalism" may damage the friendly relations between different nations. To check this insidious trend requires efforts to enhance mutual trust, dispel suspicion and seek a common understanding of history. The governments, media outlets and scholars of the countries are all expected to shoulder responsibilities.

The author is director of the Institute of Modern History, the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences, and head of the Chinese committee of the China-Japan joint history study

(Beijing Review April 10, 2007)