| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

| Writers from the 1980s: A Golden Generation Tarnished |

| Adjust font size: |

Jiang Fangzhou, born in 1989, published her first novel Rainbow Rider last year. In an interview, she rejected the label of "post-1980s writers," which she saw as a "scandalous" name. The "post-1980s writers" is a specific phrase in China describing the group of literature rookies born in the 1980s and who have written some real gems in recent years. However, this group of writers has come under attack by critics and older writers due to their overnight fame and fortune. Of course any hint of jealousy would be vehemently denied, and replaced with accusations of producing low-quality books to make a quick buck. The situation is also worsened by the presence on the market of several copycats.

Guo Jingming stands out as a good example. He was accused last year of plagiarizing other's work and of copyright infringement. Even after being ordered to disburse 200,000 yuan in damages, Guo's persistent refusal to apologize and to admit guilt drew further public outcry. Far from being overwhelmed, the 24-year-old has been publishing his Top Novel, a fiction monthly magazine, since last November. One of the post-80s' generation was also embroiled in Han Han, arguably the most famous young writer in In 2004, close to 1,000 "post-1980s writers" published their works, nearly 100 of whom met with popular success. In 2006, the number shrunk dramatically with no more than 10 still at the top. What factors led to this downturn? Last year, Nanjing Daily researched the subject, its findings concluding that 90 percent of the published post-80s writers have stopped writing altogether. About 70 percent are reduced to aiding publishers to "piece together" books or are employed as ghost writers, earning 1,000-2,000 yuan a month. An official from the Hunan Literature and Arts Publishing House admitted that without any market support, they would indubitably be turned away by publishers. The vicious circle is therefore completed since without publisher backing, Chinese readers will dismiss these young writers, even those who once drew critical acclaim and public success. The Seventh Congress of Chinese Writers was held in November 2006, without a single post-80s writer on the name list. "I don't care about things like these official writers' congresses or associations; I don't care if these old men accept me. Their formalism doesn't concern me. I just use my words to record my life, and find those who understand me," Teddy Carey, a 24-year-old writer, told China.org.cn. He published his first book, Pretty Boys, in November 2005 and should release his second after the Spring Festival. "Any literary creation will have its readers," he added, expressing his desire to persevere in his writing career in the future. His attitude may just reflect that of his generation, unlike any other Han Han is another typical figure. When he discovered that famous writer and literature critic Bai Ye had penned some unfriendly comments about him and his generation in a blog post last February, he struck back. Han Han's series of harsh articles derided classical Chinese literature circles "as meaningless and corrupted", adding that older writers and critics are standing in the way of younger ones. The debate continued while other famed figures from the worlds of literature, movies and music as well as thousands of netizens joined the fray, in itself becoming a national cultural phenomenon. Finally, Bai Ye shut down his blog for good. Han Han won, and was acclaimed as a hero for daring to stand up to the old, the powerful and the traditional. Ironically, Han Han has moved away from the forum literary. Aside from becoming a semi-professional car racer, he has tried his hand at singing and part-time blogging. However, the blame should also lie with publisher who speculated in the business and hype, toying with the livelihoods of young writers, building up expectations when few real prodigies were to be found.

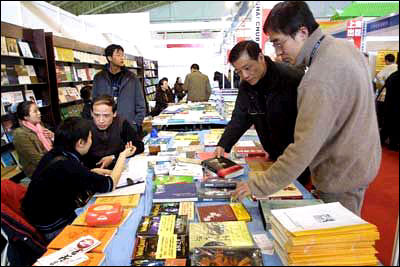

Zhi An, literature critic and deputy chief editor of New Star Press expressed his pessimism for the future of the publication industry to New Century Weekly on January 9. "Now, the market-oriented industry only cares about the short-term hype, not the long-term effect. Publishers fawn over readers by catering to general interests, but the overall quality of books is declining. It took one year to prepare, edit, print and publish a book before, but now, many books are ready in one or two months. It is stupid." He had to admit that post-80s "youth novels" containing too much trendy sentiment and similar themes remained best sellers on the book charts. Other bestsellers include those receiving props from the Internet through blogs, and on TV programs. "Among the 200,000 books published every year, only one to five percent could be said to be good. Readers have to use their own judgment to find the right ones," Zhi An said, and expressed his sadness once again. Zhang Yueran is the first post-80s writer to indulge in a spot of self-reflection. On her blog, she wrote: "Before I understood all those things, I was made a 'star writer'. All my previous works were led by various powers down a road of flaunts and uproars. Many fellows of mine are scheming, they don't care about consequences and look for made-up honors. It is always so easy for us to ignore or forgive or even indulge our faults, as if running towards an evil Utopia. Did any one of us really realize that this road would never lead us to true literature and our initial dreams? ... We are commercial instruments exploited by various people to make money; we are entertainment tools used and played by media and critics... Finally, we inevitably go to a state of suicide: make up more meaningless honors for ourselves and play various games which have nothing to do with literature..." But An Yiru, though rocked in scandal, continued to defend post-80s writers when she accepted an interview for New Century Weekly's latest issue in 2007. "The media don't say good things on post-80s, but generally speaking, I feel they have not done anything outrageous. What they write may not be classic, but these books do attract younger kids to read, which is better than smoking, drinking and hanging around bars." Where does the future lie for post-80s writers, in both East and West? Some say they are still growing. If not, they will soon be replaced by the new crop of "post-90s" writers who have already shown their prowess. For example, a 13-year-old From a Western perspective, the phrase "post-80s writers" carries little meaning. Unlike The above examples of the alienation of younger writers would strike Western readers as peculiar and destructive. Although it is understandable to try and maintain the quality of overall literary creation by weeding out novels of lesser skill, the over-reliance on older writers and their macho harassment of any seemingly threatening their place could prevent and discourage the rise of a new generation in an industry always needing fresh blood. An old English saying, "from the mouth of babes," signifying the truth that is often spoken by children not yet exposed to the world of lies created by adults takes on particular relevance in this light. No suggestion is being made that young children should be published for their own sake but allowing fresher viewpoints and opinions, which can only truly be expressed by younger people, is essential for any nation's literary heritage to avoid dwindling into irrelevant obscurity. On both sides of the

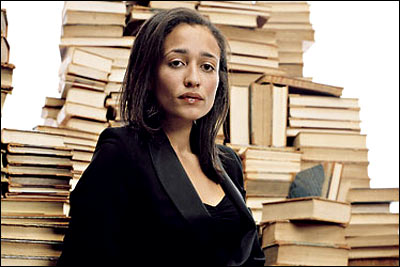

Christopher Paolini Paolini, 23, is currently writing the third book of his Inheritance trilogy, the first book of which, Eragon, has already been made into an eponymous movie, starring Edward Speelers and Jeremy Irons. Paolini published Eragon at the age of 19 and while such success is inspiring, coming from one so young, critics and readers alike have not spared the rod when chastising his work. Although his fantastical novels have met with success among children, the industry at large has not been so receptive. Although both of Paolini's books, Eragon and its sequel Eldest have topped the New York Times Bestsellers' List, accusations have flown concerning his work's highly derivative nature. Early on in the movie version's development, Elizabeth Gabler, president of Fox 2000, a division of 20th Century Fox, said of Eragon: "We found the core relationship between a boy and a dragon who share a telepathic connection a strong concept for a movie." Worthy praise for a movie executive trying to stir up interest in their newest film. However, she went on to admit Paolini's use of Tolkien fantasy elements such as a world populated by elves and dwarves, both created in Lord of the Rings. Paolini also drew heavy inspiration from the plot of Star Wars in building the story, with a young boy dreaming of becoming a mystical Dragon Rider while seeking to avenge his murdered uncle. In contrast, across the pond in Born from Jamaican and English ancestry, she represents a facet of a revitalized, multiethnic Her debut novel, White Teeth, gathers a cast of colorful and emotionally complex characters, exploring the issues of religion, ethnicity and social status that resonate throughout modern British society. Exploring issues of what is commonly called "post-colonialism", Smith succeeds in truly mastering the art of putting across affairs of colossal complexity in simple and powerful tones.

Zadie Smith To claims that White Teeth carried heavy influences from Smith's experiences, she was quoted in the Guardian as responding: "White Teeth is not really based on personal family experience. When you come from a mixed-race family, it makes you think a bit harder about inheritance and what's passed on from generation to generation. But as for racial tensions -- I'm sure my parents had the usual trouble getting hotel rooms and so on, but I don't talk to them much about that part of their lives. A lot of it is guesswork or comes from reading accounts of immigrants coming here. I suppose the trick of the novel, if there is one, is to transpose the kind of friendships we have now to a generation which was less likely to be friends in that way." When comparing the fate of young Chinese writers to the success oft met by their British and American counterparts, some fundamental differences must be outlined. The sheer numbers of novels published annually in The best summary for the plight of a young writer may have been given by Jules Renard when he wrote: "Literature is an occupation in which you have to keep proving your talent to people who have none." (China.org.cn by Zhang Rui and Chris Dalby, January 15, 2007)

|

| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

|

| Related Stories |