| Home / Spring Festival 2007 / Related Festivals | Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

| Little New Year: Busy Preparations |

| Adjust font size: |

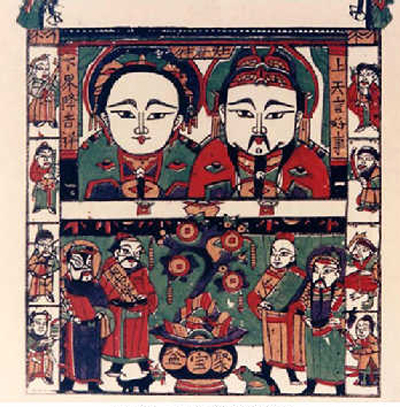

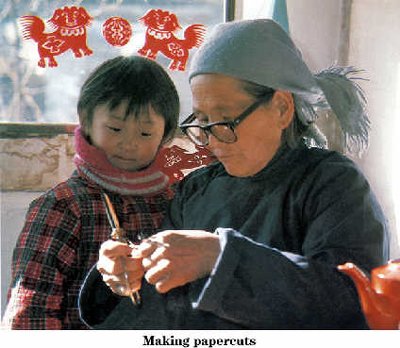

Little New Year, which falls about a week before the lunar New Year, is also known as the Festival of the Kitchen God, the deity who oversees the moral character of each household. In one of the most distinctive traditions of Spring Festival, a paper image of the Kitchen God is burned on Little New Year, dispatching the god's spirit to Heaven to report on the family's conduct over the past year. The Kitchen God is then welcomed back by pasting a new paper image of him beside the stove. From this vantage point, the Kitchen God will oversee and protect the household for another year. The close association of the Kitchen God with the Lunar New Year has resulted in Kitchen God Festival being called Little New Year. Although very few families still make offerings to the Kitchen God on this day, many traditional holiday activities are still very popular. Studies of popular Chinese religion indicate that the Kitchen God did not appear until after the invention of the brick stove. The cooking stove was a fairly late development in the history of human civilization. Ancient writings indicate that the Fire God, the earliest form of the Kitchen God, was worshipped long before the stove was invented. Zhu Rong, China's ancient Fire God was a popular folk deity and had many temples built in his honor. Stone lined fire pits, an early form of the brick stove, are still commonly used among China's ethnic minorities. People in these regions make offerings to the Fire Pit God. The Kitchen God appeared soon after the invention of the brick stove. The Kitchen God was originally believed to reside in the stove, and only later took on human form. Legend has it that during the Later Han Dynasty, a poor farmer named Yin Zifang was making breakfast one day shortly before the Lunar New Year, when the Kitchen God appeared to him. Although all Yin Zifang had was one yellow sheep, he sacrificed it to the Kitchen God. Yin Zifang soon became rich. To show his gratitude, Yin Zifang started sacrificing a yellow goat to the Kitchen God every winter on the day of the divine visitation, rather than during the summer as had been customary. This is the origin of the Kitchen God Festival, or Little New Year. There are numerous customs associated with honoring the Kitchen God and determining the date of the Kitchen God Festival, or Little New Year. The date of this holiday was sometimes assigned according to location, with people in northern China celebrating it on the twenty-third day of the twelfth lunar month, and people in southern China celebrating it on the twenty-fourth. The date of Little New Year was also traditionally determined according to profession. Traditionally, feudal officials made their offerings to the Kitchen God on the twenty-third, the common people on the twenty-fourth, and coastal fishing people on the twenty-fifth. The person officiating at the sacrificial rites was generally the male head of the household. The evening before Little New Year, the image of the Kitchen God that has been overseeing the household for the past year is taken down from its position by the stove. While the image is dried in preparation for burning, offerings and firewood are prepared. The firewood may include bundles of pine, cypress, holly, and pomegranate twigs. A new image of the Kitchen God is purchased, and figures of horses and dogs are plaited out of sorghum stalks. The offerings include pig's head, fish, sweet bean paste, melons, fruit, boiled dumplings, barley sugar, and guandong candy, a sticky treat made out of glutinous millet and sprouted wheat. Most of the offerings are sweets of various sorts. It is thought that this will seal the Kitchen God's mouth and encourage him to only say good things about the family when he ascends to Heaven to make his report. The Kitchen God will be invited to sit in a sedan chair for his trip to Heaven. Consequently, the day before Little New Year, streets and alleyways everywhere are full of vendors selling paper-mache sedan chairs and paper gold and silver ingots for the Kitchen God's journey, and singing songs in his honor. When a family makes offerings to the Kitchen God, it is in the hopes that he will ask Heaven to protect their household. According to an old maxim, "In Heaven good deeds are reported, on Earth safety is ensured." The new image of the Kitchen God is not pasted up until Lunar New Year's Eve or New Year's Day, in a ceremony known as "welcoming back the Kitchen God." According to a saying from southern China, "On the twenty-fourth day he ascends to Heaven; on New Year's Day he returns to Earth." Between Laba Festival, on the eighth day of the last lunar month, and Little New Year, on the twenty-third day, families throughout China undertake a thorough house cleaning, sweeping out the old in preparation for the New Year. Why do people clean house during the last month of the year? According to Chinese folk beliefs, during the last month of the year ghosts and deities must choose either to return to Heaven or to stay on Earth. It is believed that in order to ensure the ghosts and deities' timely departure, people must thoroughly clean both their persons and their dwellings, down to every last drawer and cupboard. Furthermore, as New Year's Eve approaches, all family affairs must be put in order, in order to ensure a fresh start in the New Year. Spring Festival falls during the off-season for farming, making this a convenient time of year for a thorough house cleaning. New Year's cleaning includes organizing the yard, as well as scrubbing the doors, windows, and interior of the house. Old couplets and papercuts from the previous Spring Festival are taken down, and new window decorations, New Year's posters, and auspicious decorations are pasted up. Preparations for Spring Festival include stocking up on necessary provisions. At noon on New Year's Eve Day, shopkeepers everywhere put up their shutters and lock their doors, not to reopen until the end of Spring Festival several weeks later. Therefore, everything needed to make offerings to the ancestors, entertain guests, and feed the family over the long holiday must be purchased in advance. Before setting out to the market, a Spring Festival shopping list must be made, including items such as meat, poultry, and eggs; fruit and vegetables; rice and flour; cigarettes, alcohol, sugar, and tea; red paper, images of celestial horses and the Kitchen God, incense and candles, snacks, new calendars, and toys. Also not to be forgotten are new clothes for the children and firecrackers to welcome in the New Year. After the Spring Festival provisions have been brought home, it's time to make further preparations for the holiday. These may include preparing meat, packing blood sausage, making tofu, steaming New Year's sticky rice cakes, and making fried bread. This must all be done in advance, since no cooking may be done from New Year's Eve until well into the first month of the New Year. As a result, starting at Little New Year, families everywhere are caught up in preparations for the New Year's holiday. A saying popular in Beijing vividly expresses the holiday spirit of China's Spring Festival: "Eat sticky candy on the twenty-third; sweep clean the house on the twenty-fourth; fry up tofu on the twenty-fifth; stew some mutton on the twenty-sixth; kill the rooster on the twenty-seventh; set dough to rise on the twenty-eighth; steam mantou buns on the twenty-ninth; stay up all night on New Year's Eve; pay holiday visits on New Year's Day."

(China.org.cn February 13, 2007) |

| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

|

| Related Stories |