| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

| Brewing Culture |

| Adjust font size: |

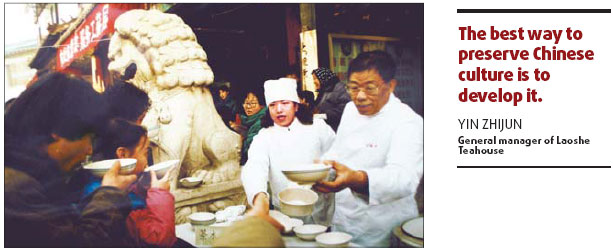

On a big white screen in front of a hall decorated with traditional Chinese lanterns, tables and chairs, the Monkey King springs into the air and attacks the demon with his golden cudgel. To the accompaniment of local opera music and drumbeats, the demon retorts with a mouthful of fire. Among the enchanted audience, Charlie Yang, a Chinese-American film producer from Hollywood, marvelled at the magical art of the ancient piyingxi shadow play: "It can be thought of as the oldest movie! It is an excellent expression of multi-media, with sound, light and shadow." Yang is among hundreds of thousands of overseas guests drawn to the Laoshe Teahouse, a unique venue where patrons can drink up gallons of tea and a sea of genuine folk culture. Upon entering the teahouse, every visitor is greeted by a life-size photograph of former United States President George Bush with the founder of the teahouse, Yin Shengxi, hung in the entryway. When Yin led a dozen unemployed youngsters to open a simple tea stand to the south of the Tian'anmen Square in 1979, little did he or anyone else imagine that someday they would entertain such foreign dignitaries as former US State Secretary Henry Kissinger, former Japanese Premier Toshiki Kaifu and ex-Kuomintang Chairman Lien Chan.

Furnished with a few tables and big teapots, the tea stand offered passers-by a big bowl of tea boiled with low-grade leaves. Visitors could also enjoy tanghulu (a sugar-coated hawthorn), photos of stars and small electric appliances. "I often finished a breakfast at 0.10 yuan (about 1 US cent): 0.02 for tea and 0.08 for a pancake," Yin Zhijun, daughter of Yin Shengxi and general manager of the teahouse, said, recalling her childhood. Through a decade of hard work, the tea stand finally generated enough money for the three-story building, which came to be known as "Laoshe Teahouse".

All of Lao She's works shine with a genuine concern for common people, and every time Teahouse is staged, the theatrical drama is always a sensation. Naming the teahouse after this writer is a fitting commemoration and gives the teahouse a deeper purpose than just a place for recreation. Lao She's son Shu Yi gave the teahouse a novel manuscript sample of his father's writing, which read "Beijing Big-Bowl Tea" (Beijing Dawancha), for the teahouse to make a sign. Hu Jieqing, Laoshe's wife, signed for the teahouse. From the very beginning, Yin Shengxi believed in the magical charm of traditional culture. The former headman of a supply and market team of the Dashilar neighborhood community grew up in a family fond of folk operas. However, enthusiasm didn't bring booming business immediately. By 1995, the teahouse had racked up 25 million yuan ($3 million) in debt, Yin Zhijun said. The teahouse had to confine its operation to the third floor and lease the first and second to clothing and utensil dealers. "It was the most difficult period," recalled Yin Zhijun, who succeeded her father after he passed away in 2003. "Disco and karaoke bars were very fashionable. It seemed that few cared about traditional culture."

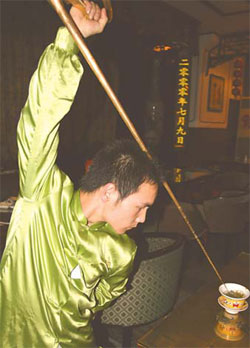

With very few places to perform, many old folk artists found Laoshe Teahouse to be their last haven. At times the hall was empty except for the teahouse's staff, but they persisted. Their persistence finally paid off when Kissinger visited the teahouse in 1992, followed by George Bush in 1994. These visits rocketed Laoshe Teahouse's reputation as a hotspot for overseas tourists. However, the teahouse still suffered from inefficient management, as did other State-owned or collective enterprises in the early 1990s. When Yin Zhijun graduated from college and became a waitress at the teahouse in 1993, she found many colleagues would chat, weave sweaters or even go out to buy vegetables during shifts. In 1996, an actor with the Beijing People's Art Theater, where Teahouse is staged, was so angry at the cold faces that he swept the teapot onto the floor. "I realized we had to improve our service," Yin said. She fired the incompetent staff, including some who had worked there since 1979. Every year, two or three newcomers will replace those employees who ranked last on the competence evaluation. She also attaches great importance to training employees to be skilled in the performance of the tea ceremony, English and computers. Elected as general manager in the wake of SARS, which dealt a heavy blow to the capital's tourism industry, the gentle but resolute woman stood firm in the face of criticism. She reclaimed the leased-out lower floors and spent more than 1 million yuan ($125,000) adding more traditional factors to the teahouse. The first floor now features a stage where traditional Chinese shadow puppet plays and folk music are performed as guests sip tea and chew local snacks prepared by famous chefs. Chinese opera fans, young and old, gather here to applaud their beloved stars. The second floor has become a siheyuan courtyard decorated with pumpkins, broomcorns and red peppers, which symbolize wealth and auspiciousness. Inside, Chinese tea ceremonies are performed. The rough bowls of the early days have been replaced by exquisite tea ware. Sancaibei, or three-talent-cup, has a lid which is said to represent the sky, a cup signifying mankind and a saucer representing the earth. Together, the set illustrates the ancient philosophy of tian ren he yi, or humanity in harmony with nature. When drinking, one should hold the saucer with the left hand, lift the cover with the right thumb and middle finger to brush away tea leaves. A small sip shows good manners and leisurely joy. The third floor caters to guests who are interested in traditional shows, including Peking Opera, cross-talk comedy, magic, acrobats, face-changing and martial arts. Performances are staged every night from 7:30 to 9:20. "I don't know how they did it; it's a wonderful experience," David Beever, an investment banker from London, said upon a recent visit. Beever had been invited onstage as a volunteer to help the magician tie up his assistant. He put on a silk coat and was enveloped in a curtain along with the assistant. When the curtain was lifted seconds later, the assistant was wearing the silk coat, with her arms still tightly bound. "I didn't feel a thing," Beever said. "What a brilliant trick the magician did! The performances are stunning and very different from what I expected." "The best way to preserve Chinese culture is to develop it," said Yin, who always looks for high-quality folk arts for her customers. When Lien Chan visited the teahouse in 2005, he was very impressed by the performances and the special Dafo Longjing Tea, which Yin chose from Zhejiang Province. Lien wrote a couplet: "Booming tea culture, harmonizing affections across the Straits". "My father didn't believe that Chinese culture, which has endured for thousands of years, would become outdated," Yin said. Her father passed away at 65 because of diabetic complications. "He had been striving for decades to revive our traditional culture. For me, the greatest joy is that I can continue his work." (China Daily April 24, 2007) |

| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

|

| Related Stories |

|