| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

| The Art of Darkness |

| Adjust font size: |

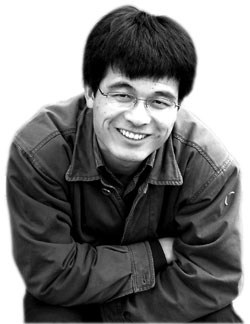

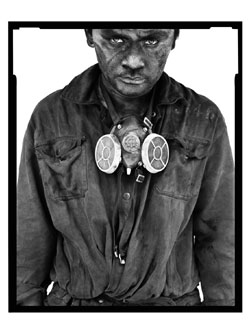

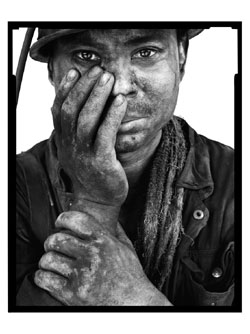

Song Chao knows two kinds of darkness well the blackness of mine shafts and that of darkrooms. His most well-known works are the black-and-white portraits of coal miners. The pure white background of his photographs provides a striking contrast to the miners' faces covered in coal ash, but the men all seem relaxed and present their true selves in front of the camera. The 28-year-old photographer has managed to coax this genius from his subjects because he himself once labored 430 meters below the ground for six years. The former miner is now a postgraduate student at Beijing Film Academy's photography department, an incubator of China's best photographers. What is most appealing about Song's miners series, first shown in Beijing in 2003, is a glimpse into the lives of a group of little-known people. "For the public, the appeal comes from the warmth, intimacy and strength of the photographs, which is due to Song Chao being a miner himself," said Alain Jullien, an internationally acclaimed curator who introduced Song to the 2003 Arles International Photography Festival. Now the Pompidou Center and China's National Museum have collected some of his works. His exhibitions in Beijing's 798 art district and in France as part of the Year of China in 2004, created a stir. Song's photos bespeak a tender affection for his old buddies and the miners' unique lives. He never asks his models to strike a particular pose or wear a particular expression. "They just stand or sit the way they are, and what I do is to catch that expression that best reflects their personality," he said. The pure white background, says Song, is aimed at removing all distractions and allowing the miners to speak directly with the viewers. A miner's life

Life as a coal miner is not as dreary as many imagine. Song and his colleagues were kept well aware of security concerns. Every day before the miners went down into the shafts, they would learn how to protect themselves and take family photos along to remind themselves to be cautious. In the smell of coal and sweat, and the heat generated by machines, Song and his colleagues worked half-naked around the year. The coal ash and engine oil would stick to their skin. They had to use a brush to clean their nails. "It was a carefree life," Song recalled. "But something in my nature is always pushing me to change. I am always ready for new things." New direction

Knowing his interest in photography, Song's brother introduced him to Hei, who was moved by the young man's enthusiasm. "He asked me all kinds of questions, and said he wanted to lead a different life," Hei recalled. "Photography was the best way I could think of to enter the outside world," Song said. Hei suggested Song capture the group of people he was most familiar with. And Song took his advice. Hei sharply criticised Song's first effort, because the photos were not even in focus. Hei suggested Song get a new camera and try again. While shooting the second batch of pictures, Song journeyed between Shandong and Beijing eight times in a year to confer with Hei. His efforts were rewarded when Hei called to say his miners' series was good enough for a solo exhibition. In 2003, Song's exhibition opened at Beijing's 798 Photo Gallery, an avant-garde venue at that time. The reactions went beyond his wildest expectations. Photographers and scholars even held a seminar on his works. Soon he received a call from Alain Jullien, took leave from the mine and flew to Paris. His wildest dreams came true and once in France, he became a star with Western audiences. Song, a shy and restless man of medium stature, is now zooming in on new subjects: the miners' families, doctors, teachers and other members of the miner community. "This community embodies the disharmony between humans and resources," he said. The mine Song worked for was supposed to have enough coal for 80 years. But at current rates of use, it will be depleted in 50 years. Song quit his mining job in 2003 and signed up for courses at the Beijing Film Academy. He then undertook postgraduate studies at the national academy. On Discovery

The film was made for a competition initiated by Discovery Channel. But Song turned down the offer despite its promise of greater fame. "Many people thought I was silly," Song said. Discovery agreed to postpone the shooting till Song finished the exam. The film was selected as one of the top six documentaries in 2005 and Discovery is airing it worldwide. Song has been compared with the German master August Sander (1876-1964), who was also a miner. "They are just kidding," Song smiled. "What I always believe is this: Photography is just a way of saying what I am thinking." (China Daily January 15, 2007) |

| Tools: Save | Print | E-mail | Most Read |

|

| Related Stories |

|

Product Directory China Search |

Country Search Hot Buys |