Why and How the CPC Works in China

0 Comment(s)

0 Comment(s) Print

Print E-mail

China.org.cn, June 30, 2011

E-mail

China.org.cn, June 30, 2011

War-torn economy

The economy of China taken over by the CPC from the KMT in 1949 was in a state of extreme backwardness. There was an acute shortage of industrial products, and agriculture was still at the level of hand-cultivation and dependence on the weather; transport was backward – relying on animal-drawn vehicles and wooden sailboats; posts and telecommunications technology and equipment were backward; telegraphs and telephones were mostly operated manually; about half of the country's counties did not have automatic telephones, while about a quarter of them had no access to the telegraph system or long-distance telephones; the central and western regions were generally in a very isolated state; there was a severe shortage of goods on the market, and the problem of food and shelter for most of the people was still to be resolved.

The Japanese invasion of China and the KMT government's overall financial and economic collapse had put the already very backward agricultural and industrial production of China into a primitive state. Compared to the yield before the Japanese invasion, in 1949 the output of coal had been reduced by more than half, that of iron and steel by more than 80 percent, and that of cotton textiles by more than a quarter. In general, the average industrial production had shrunk by about half. Moreover, the rural part of the majority of the newly liberated areas suffered from bankruptcy, floods and droughts.

The national food production was 21 percent lower than before the war; cotton production was equivalent to about 54.4 percent; and the number of farm animals had shrunk by 16 percent. Railway, highway and other transportation methods in various places were severely damaged due to long and chaotic years of warfare. Urban and rural exchanges were almost cut off, and the market was depressed. According to the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific, China's per capita income in 1949 was US$27, which was less than half of that of India, and only about two-thirds of the average of other Asian countries.

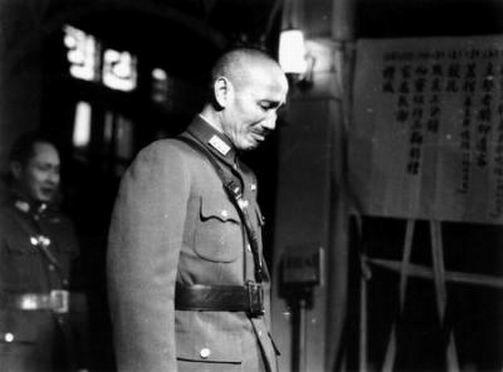

In addition, at the end of 1948 Chiang Kai-shek ordered the Central Bank to transfer some US$500 million-worth of gold, silver dollars and foreign currencies to Taiwan. On December 1, the KMT's Central Bank transported the first batch of two million taels (a unit of weight for silver or gold, about 31 grams) of gold to Taiwan, followed by 10 million yuan-worth of silver dollars south to Guangzhou. In January 1949 the bank transported to Xiamen 570,000 taels of gold and 22 million yuan-worth of silver dollars.

When Tang Enbo, the KMT's commander-in-chief of the Beijing-Shanghai-Hangzhou Garrison, fled from Shanghai, he absconded with 198,000 taels of gold and 1.46 million yuan-worth of silver dollars from the Central Bank. After the liberation of Shanghai, when the KMT's Central Bank was taken over by the CPC, there were only 6,180 taels of gold, 1,546,643 silver dollars, and a small amount of foreign currencies left there.

Meanwhile, the KMT government also evacuated to Hong Kong 29 monopoly enterprises in the fields of aviation, finance, trade and others. The net assets of these enterprises were about HK$243 million in all. A large number of trained and experienced professionals were also transferred by the KMT from the mainland to Taiwan. The evacuation of large amounts of funds, materials and qualified personnel increased the difficulty of the recovery of the economy after the founding of New China.

Thus, on the occasion of the birth of New China what the CPC was facing was a grim situation of serious recession and overall decline of the national economy. This was most prominent in the country's then most affluent areas of Shanghai, and Jiangsu and Zhejiang provinces.

Because of a serious shortage of funds and materials a large number of enterprises could not even sustain simple reproduction, much less expand. In the large industrial city of Shanghai, at the time it had just been liberated, the stock of coal was enough for one week's use only, and the stocks of cotton and grain were not enough to last a month. Among the city's more than 10,000 private factories, only a quarter were in operation. The cotton textile industry, which had been relatively prosperous, could operate only three days and nights per week.

The mess left by the KMT government included a weak industrial foundation; finance and economy were on the verge of collapse; inflation was out of control; and speculation was rampant.

Go to Forum >>0 Comment(s)